Postcards from Las Vegas, NM and Winslow, AZ - “The Footprints of Fred Harvey”

Michael Wallis has famously said that Route 66 is for travelers, not tourists. As he tells it, "tourists like the familiar, tend to gawk at culture from afar, and generally like to cram as much into their agendas as possible provided it’s cheap, safe and by all means comfortable. Travelers, on the other hand, hanker for the hidden places and in making new discoveries often discover a thing or two about themselves." At the same time, it merits acknowledgement that this ethos is perhaps easy to embrace today because, "the friendly skies" notwithstanding, travel is generally as comfortable and easy as it's ever been. There are many forces and people responsible for bringing us to this point, but in America, and most specifically the American West, perhaps the first to lay the groundwork was restaurant and hotel magnate, Fred Harvey. His is a name that Hollywood and Judy Garland immortalized in a 1946 musical, and one that still today has a way of popping up along Route 66’s western stretch. In this episode, through visits to two of Fred Harvey's surviving properties, and conversations with author Stephen Fried and surviving Harvey Girl Beverly Ireland, we’ll learn a little about the man behind the name, and how the brand and empire he created not only elevated outlaw country, but helped give us Americans an appreciation for our own culture in the process.

TRANSCRIPT

(As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos, spelling and grammatical errors)

________________________________________________________

Evan Stern (00:00):

Hey y'all, Evan here. If you heard the last episode, you might remember I said I left Tucumcari feeling less like a tourist, more like a traveler, which is a distinction Michael Wallis laid out for me in our first conversation. As he tells it, tourists like the familiar tend to gawk at culture from afar and generally like to cram as much into their agendas as possible, provided it's cheap, safe, and by all means comfortable. Travelers on the other hand hanker for the hidden places. And in making new discoveries often discover a thing or two about themselves. Now this is an ethos I feel I've embraced for a while, and is one I'm quick to espouse, but a backpacker I am not. And if I'm being truthful with myself, the reason I can get away with this attitude is precisely because, well, the so-called friendly skies not withstanding traveling is as comfortable and easy as it's ever been.

Evan Stern (00:53):

Now there are many forces and people responsible for bringing us to this point, but in America and most specifically the American West, perhaps the first to lay the groundwork was restaurant and hotel magnate, Fred Harve., His is a name that Hollywood and Judy Garland immortalized in a 1946 musical and one that still today has a way of popping up along Route 66's Western stretch. And today we're gonna get to know a little about the man behind that name and how the brand and empire he created not only elevated outlaw country, but helped give us Americans an appreciation for our own culture in the process. I'm Evan Stern and this is Vanishing Postcards.

Sean Williams (02:51):

The other Las Vegas is around because they took our name because we were such a rowdy gambling, drinking and brothel type town that they actually copied our name. Las Vegas means the meadows, the grasslands start right here at the edge of town. That's why we were named Las Vegas. So the other Las Vegas in the middle of the desert, they took our name. Literally they only exist because of us and that name.

Evan Stern (03:13):

A lot of people don't know there's a Las Vegas in New Mexico. It sits in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo an hour and change before Santa Fe about six miles north of 66's original alignment. A charming town with an old plaza and 900 buildings on the National Register of historic places, its elevation is not only higher than Denver's, but native Sean Williams tells me its importance once exceeded that of Colorado's capital.

Sean Williams (03:39):

Back in the late 1800s, this was a very big city. This was one of the biggest cities in the southwest. Um, we were one of three cities that had an electric trolley run through town. Um, we were bigger than Denver, bigger than Albuquerque, so this was the place to come, believe it or not. In the 1800s, this street right here, Railroad Avenue was basically bars, brothels and hotels. There was a number of illicit businesses here on this side of town. Uh, the railroad mostly brought in a lot of bad guys and they would hang out in the places here and it, it got to be a very dangerous place. Um, in fact, in the 1800s they posted a notice saying if you're here after midnight on a certain day, that they're gonna have a neck tie party for you up at the plaza at the hanging windmill. Oh, in fact, Doc Holidays', dentist office was right around the corner from us here. He was, you know, a hundred yards away from us and he had a saloon right at the corner. And you know, Teddy Roosevelt and the rough rider actually had their first reunion after the Spanish American War Here in this hotel,

Evan Stern (04:35):

This hotel were speaking in is the Castaneda which Sean oversees as property manager and helped reopen in 2019, following 70 years of abandonment.

Sean Williams (04:45):

The interesting story is, uh, a lady and her husband bought it in the seventies and their plan was to remodel it. Well, he died fairly early on after they got it and she just lived here for 40 some years just operating the little bar right in here called The Nasty Casty. That's what it was to me when I was growing up. So she lived up in the corner room up above us here and that's it. It was her living here and the bar and the rest of the building was just basically abandoned

Evan Stern (05:09):

Standing in its gleaming lobby of pressed wedding cake ceilings and polished wooden floors, no dereliction is noticeable today. Built in 1899, its Bell Tower overlooks a U-shaped mission revival courtyard. And as Fred Harvey's first Trackside Hotel, some say it not only changed rough and tumble Las Vegas, but the American perception of the West.

Stephen Fried (05:34):

Fred Harvey had an idea, I think that he understood America better than Americans did because what he knew was that he had come to America, he was very excited about America and what he saw was wealthy Americans, that as soon as they had money, they wanted to go travel in Europe. Um, cuz that's what people did then. But what he believed and what the railroad people believed was that eventually people would see different parts of America as being as interesting, exotic, and fascinating as the, as the places that you went in Europe. And they taught the people in the company to be, to think that way about the food, about the history. One of the things that's important about the Harvey Company is that they're not just places to sleep and stay. They are places where early western tourism takes place, where the first generations of people who come to the West to see the Grand Canyon, to see the Native American Pueblos, they are, uh, taught by people who are in the Fred Harvey company's employee about the real story of the West. That is something that was really invented by them and uh, it's really, it's quite fascinating and makes the company interesting to look at, not only because of who they fed, what food they had, who worked for them, but the role they had in, um, as, as one, uh, Native American writer said, introducing America to Americans.

Evan Stern (06:46):

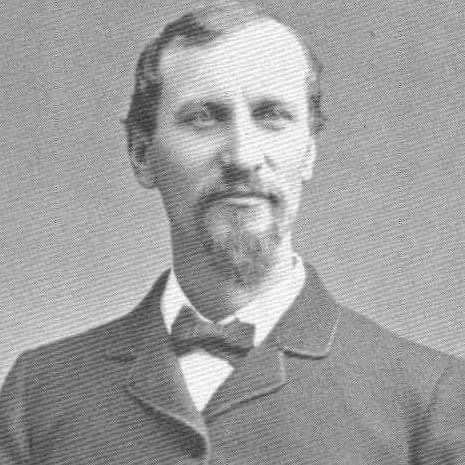

That's Stephen Fried. A Philadelphia based author, historian, reporter and journalism professor, he devoted years to studying Fred Harvey and his namesake company after noticing his portrait at the Grand Canyon's El Tovar Lodge. This fascination resulted in the publication of his acclaimed book, Appetite for America, which begins by asking the question, "Who the hell is Fred Harvey?" In short, he was an English entrepreneur who after scrubbing pots in New York City kitchens made his way to St. Louis, where he opened a cafe of his own before ascending the Hannibal and St. Joseph's railroad's corporate ladder. In 1876, having recognized a need to feed passengers out west, he struck a sweetheart, handshake deal to manage eating houses for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe rail lines. In doing so, an empire was born that at its peak boasted over 65 restaurants, a dozen large hotels, 60 dining cars and gift shops everywhere from Chicago and San Francisco to Slayton, Texas and Needles, California. Stephen says he was essentially the founding father of American service. Ray Kroc before McDonald's, JW Marriott before Marriott Hotels. And his company, which outlasted him by nearly 70 years, was Coca-Cola before Coca-Cola.

Stephen Fried (08:05):

So keep in mind, the only reason there were Trackside dining rooms, and they were mostly in the west because in the east there were dining cars- But in the west, west of Chicago, the railroads all agreed not to have dining cars because they were too expensive to travel over long distances. So they agreed to have eating houses. They were all terrible because they were run by local people and they knew the local people knew they would never see 95% of the people on the train again. So there was no reason not to serve them crappy food right before they got back on the train. If they took a bite of it, you know, then just, you just cut off the part where they took a bite and then you could serve it to the next person who's gonna know. Um, there was a story famous story in the New York Times about how, um, this food and the Western Railroad stations was more dangerous than train crashes, uh, or bridge collapses or fires.

Stephen Fried (08:51):

And so it was a well known thing. It was one of the downsides of traveling in the West because everybody knew that the railroads existed primarily to move goods. They, they hated people. You know, the people were just too much of a pain for them. It's part of the reason why the Pullman company was given the responsibility to run all the dining car, all the sleeping cars, because the railroads wanted nothing to do with the, with the people. And the Fred Harvey Company was one of the companies that was given responsibility to take care of the feeding because of that. So these Harvey restaurants initially were just in whatever the train stations were. You know, railroads would build some tracks, they would build a wooden building, they were small, they had a ticket window, they had a waiting area, and they had a area that could be a restaurant. The Santa Fe Railroad

Stephen Fried (09:32):

and Fred Harvey agreed that Fred Harvey would run all of them. What you would see is a wooden train station that doesn't seem like any big deal. And when you walked into the Harvey part of it, it would be like a European hotel dining room. The tables were perfect like you would find in the best fine dining places in New York, Chicago, London. Crystal linen, uh, silver with Fred Harvey etched on it. And the food was better food than most people could get in major cities because they were bringing fresh food in from all these different places. So, and there was also a little thing that was like a little diner pre-dinner, like a curved, uh, counter and stools where you could order a la carte. And there was also takeout coffee. So we always say that, you know, with these things, originally were, were sort of like Starbucks, the version of 1888, because that's what people went to him for. Fine dining, diner dining, take out coffee that was brewed that day because in the west, most coffee was, you know, they would judge if it was brewed that week.

Evan Stern (10:26):

But while some communities now mourned the arrival of Starbucks as a harbinger of homogenization, Stephen quips, that being a fast food nation was originally a good thing as Fred Harvey's system was known to dramatically raise standards wherever they arrived. And those standards were exacting.

Stephen Fried (10:43):

You know, one of the things that was important in a company like this is they had to have rules that went across all the restaurants. They couldn't just count on individual people doing their jobs well. So they had 30 minutes to serve the people on the trains, cuz that's how long a train stop was supposed to be. So they created a system for everything to make sure they cut as many seconds out of it as possible. So the Harvey girls had, uh, a cup code to make the pouring of beverages go faster. They had a rule for everything, everything also had to be fresh. So, um, even with all this, you had to make dressing table side. You couldn't pre squeeze orange juice that'd be squeezed when the order was made and the steaks had to be cooked when people had them, they had fresh eggs.

Stephen Fried (11:23):

So it was a combination of freshness, a a perfection of service that they kept trying to make more and more perfect and make examples of people if it wasn't perfect. And then they used certain techniques to scare the employees, into not being perfect. One of them, which the story which started very early on and kept being told even after Fred Harvey was dead, that, you know, Fred Harvey would come into the place before the customers. And if he saw a chip on something or he saw a dirty plate, he would grab the tablecloth, pull it and throw the whole table up in the air, and the waitresses would have to reset the table incredibly quickly before the people waiting on the train to come eat came in. So they were, uh, very tough bosses, but always fair. There was a Fred Harvey ethos that Fred said himself and that his son Ford put down in writing later. And one of the biggest things was always, please the cranks. The biggest thing that Fred always says, Well, you don't learn anything from the people that are happy. You know, uh, what you learn from are the cranks who are unhappy about everything, uh, to find out what they're upset about, to make them happy. And if you can do that, then you were running a smart hospitality business.

Evan Stern (12:30):

This formula proved a success that distinguished the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe from other lines. And more often than not, the ones responsible for pleasing these cranks were the Harvey girls whom MGM said "conquered the West as surely as the Davey Crocketts and Kit Carsons- not with the powder horn and rifle, but with a beef steak and a cup of coffee

Stephen Fried (12:52):

In New Mexico, it was all African American men who were the waiters. And there was a lot of tension, racial tension in New Mexico, uh, around these issues, not just in the Fred Harvey restaurants. Uh, after a, a racial incident in Raton, New Mexico, which is the first place you'd come to when you cross over from Colorado, uh, Fred Harvey was convinced to change the way they did servers, um, in the restaurants. He was convinced of this by a guy who was actually his former postman, and they decided that they would start hiring single women from the Midwest and, uh, training them in the Midwest and then putting them in all the different locations so that they didn't have to rely on whoever was in town. And they decided they would change over from male servers to female servers. So by 1887, there were Harvey girls throughout and they were hiring dozens of women, training dozens of women all the time, setting them out on the trains to the different locations. And it became known, you know, it's like the early version of the modeling industry, right? If you're, if you're a woman and you want a career and you want to get out of the house and you don't want to be just married or just be a teacher and never leave town, if you want adventure, you go and try to be a Harvey girl.

Evan Stern (14:01):

Two of the more than 100,000 young women who chose to strike out west for a taste of adventure were identical twins, Bernette Jarvis and Beverly Ireland, who found work at La Fonda in Santa Fe during the company's twilight and remain in New Mexico nearly 70 years later.

Beverly Ireland (14:17):

I and my twin sister were the only two in the family, and we are farm girls from a dairy farm in Minnesota, and weren't afraid of hard work. I think that's why we fit into the Harvey Girls regime. You know, you had to know you had to be hard workers to work for them. We, uh, didn't want to go on to college, uh, after we graduated from high school, which was in, in the spring of 1955. And we were tired of cold winters in Minnesota and we had never been to Santa Fe before, but actually we just came to spend the winter. And like Bernette will tell you, it's been a long winter. Those were the days when, you know, when you left home you were on your own. And they weren't too fond of us leaving in the first place, but they, they really thought we would be back, you know, when the winter was over.

Beverly Ireland (15:21):

So when we got here, of course we needed to find work and we went to La Fonda and we said we were seeking help, asked if we had any experience, and we said, well, very little. We had worked at the, uh, Green Giant canning factory in a neighboring town at the Cantina. So Mr. Williams was a hiring man at La Fonda at the time, very, very lovely. And he said, You know, I can use some extra help. The legislation is starting here in January. We were trained by the, by the other, uh, uh, help there, the girls. It was pretty up class, you know, from what we were used to. It was, it was a good job. Like I said, it was, uh, we, uh, had to come out of the kitchen with everything on a big tray overhead, you know, and serve from the right and remove table, uh, plates and dishes from the left.

Beverly Ireland (16:33):

And, uh, then during the day when you were working, if you spilled something, uh, like coffee splashed out of the cup or something on your uniform, you were set right downstairs and got new, a new, uh, change of clothes. And, and Monte Chavis was a maitre'd d there. And I might believe, I might say he was pretty tough and we wouldn't, he wasn't always liked by many of the waitresses and bus boys there because he was so tough. But, uh, we became better waitresses. Um, I did wait on Jack Lemmon and I'll just never forget he had the biggest blue eyes and it really looked at me and I thought, Oh, I can't believe this, You know!

Stephen Fried (18:13):

Uh, Mary Colter was, um, a woman who grew up, uh, she was from Pittsburgh. She grew up in, uh, Minnesota. She was trained in, um, industrial arts and in design and had a friend who worked for the Fred Harvey Company who heard that they were gonna open a native American art museum in Albuquerque in like an empty room that existed between the train station and the hotel. And she was sent for and hired to design it. And in designing it, she basically did what we now think of as Santa Fe style, which is all these different cultural artifacts, sort of, you know, all, all in the same space. Colter came in first as a freelancer. She was unbelievably opinionated, had a brilliant eye, had a real understanding of the interface between Anglo culture, Native American culture and Hispanic culture. Wanted to make sure the people understood the art, the industrial arts, the crafts, and the stories of these cultures.

Stephen Fried (19:09):

And also was a great designer. Uh, she was not licensed as an architect, but she oversaw the architecture of all the buildings that were created from that time forward, did all the interior designs and a lot of the exterior, uh, designs as well. So we're talking about the buildings that were built after 1910. It involves, uh, a number of the buildings at the Grand Canyon and um, uh, most specifically involves, uh, La Fonda, which is created in 1926. La Posada, which created in 1929, 1930. Those are two of the three active still Fred Harvey hotels that exist. You know, she just had an incredible gift for making sure that each of the spaces that she did had strong ideas behind them, strong visual ideas behind them. Of course, if you've ever been at hermit's rest, you know, it's a, has a huge hearth that you could live in the hearth.

Stephen Fried (19:55):

But what's interesting is when they first built it, she figured out a way to make it look like there had been fires in this hearth for a thousand years. And the people at the Grand Canyon, like at the park and stuff were like, Oh, this is terrible. This thing is already dirty and you know, what are you gonna do about this? It looks like, it looks like how she's no, it's, it looks like the way it's supposed to look. And, um, she just didn't take crap from anybody. So, you know, generations of Harveys would tell you stories about how she just, you know, if they made a suggestion, she would basically tell them to go to Hell. She was gonna do whatever she wanted. You know, if you talked to anybody still alive who knew her, it's like as soon as you saw her, you were scared. If you had a question to ask her, you were really worried to ask her. Um, you were hoping she'd be funny and not mean, but she was, you know, one of the first, you know, she was a one of the first women business executives in America and she controlled the design of many, many buildings that matter a lot to people in America. And her story is still debated and it always will be.

Evan Stern (20:47):

The best architecture should tell a story. And walking me through La Posada, the Winslow Arizona resort, she proclaimed her masterpiece owner Allan Affeldt tells me of the narrative Colter created for the property.

Allan Affeldt (21:00):

Before she would design something, she would create a backstory. And her backstory for La Posada is that this is a hacienda. So she imagined this was a home of this fabulously wealthy timber and cattle baron and that, and as a home, it would've been added onto over the years generation after generation, they would add onto the building until maybe the depression came in 1930s and they sold the building to Fred Harvey who converted it to a hotel. None of that happened, of course, it was built as a hotel, but there's all those architectural elements as if the building had been expanded as a private home over a hundred years. And her whole life was creating this architectural aesthetic, which was so different from the way hotels were thought of in that day. It was architecture as an experience, it was hospitality as an experience. Now they think of the business as heads in beds and Colter was well ahead of her time in thinking about how you can create an experience that would draw people into the building and back over and over and over again.

Allan Affeldt (21:54):

There's only 54 guest rooms and it's 70,000 square feet. Um, also the setting is, I think, unique among the Harvey Hotels. This was the only property where Colter designed everything. The building, the maids costumes were different here. She designed the China. Um, and this is the only place Colter did a landscape plan. The space itself is so majestic and nuanced. There's all of these interlocking volumes. It's not like, you know, in the Victorian era, a room was a box and then there's another box and another box, and there were doors between them. In, in Mary Colter's Masterpiece La Posada,, all these rooms just flow into each other. So it's kind of a process of discovering the extraordinary architecture that was here that had been buried. So you can create this whole fantasy world

Evan Stern (22:39):

Featuring a Spanish colonial facade with arched veranda entering La Posada with its tiled corridors, frescoed walls, and vast, art heavy common spaces is like entering a fantasy world. But while Carol Lombard spent one of her last nights here, and its notable guests included Albert Einstein and FDR, its initial run as a hotel lasted a mere 27 years. It's construction in today's dollars cost somewhere north of 40 million. And as its opening coincided not only with the Great Depression, but Winslow's decline as a transport hub, the property proved to be something of an albatross for the railroad. Following the death of Fred Harvey's grandson, the dynasty came to an end after its sail to a conglomerate in the late sixties. And upon learning of La Posada's 1957 closure, Mary Colter is quoted as having lamented, "Now I know it's possible to live too long."

Allan Affeldt (23:38):

One of the great architectural tragedies is that her experience was a woman in a man's world without a license and she did not sign any of her drawings. So, um, all the architectural drawings for all of Colter's buildings are signed by some railroad engineer, and that's partly why she just vanished from architectural history. But, uh, when she died in Santa Fe in 1958, uh, apparently all of her drawings and records were thrown away. So you can imagine it would be like Frank Lloyd Wright's architect archives being thrown away. So Colter's lifetime of drawings and correspondence is gone and it will probably never be recovered.

Evan Stern (24:17):

La Posada's charming lobbies were gutted to make way for office space and like much of Colter's other work could have been lost together had Allan not read of its impending destruction in a 1994 magazine. By 97, he and his wife Tina Mion owned the property, moved to Winslow and with more passion than experience set about seeing to its remodel and reopening

Allan Affeldt (24:40):

Well, I was, um, always interested in architecture and this building was just so extraordinary and it was clear it was gonna be torn down. So Tina and I figured, well, okay, maybe we'll just learn the, learn the hotel business. So where we are, for example, there was a wall across, well <laugh>, you can't really describe it, but all these huge spaces were partitioned up and made it into little office cubicles. So all the floors were covered with vinyl, it was all acoustic tile drop ceilings. It looked like an abandoned office building or maybe an old hospital. So none of the beautiful architectural detail was here. Some of it, like these vaulted ceilings was under the acoustic tile. Uh, some of it like these beautiful stone floors was under the vinyl. So there was kind of a lot of archeology, um, to put the space back to what it was, but must of.

Allan Affeldt (25:28):

It was just destroyed. Uh, when we bought the building, it had been abandoned for so long that there were a lot of transients and street people who camped on the property and would come in the property on a regular basis, where the first two or so years, it was like night of the living dead. You know, at night when the bars had finally shut down at one o'clock, they would just discourge these drunk people, uh, out onto the streets and they would just wander around and sometimes wander into the building. And, and you know, there were a lot of business challenges too. Nobody would give us a loan first. There was no tourism here. So the notion that anyone would operate a first class hotel, let alone a restaurant in a little dusty railroad town like this was just absurd. Like to have a restaurant like the Turquoise Room here now, you know, it's considered one of the best restaurants in the southwest.

Allan Affeldt (26:13):

But when we started, there were no restaurants in downtown at all, let alone something of this caliber. One of the really important contributions these buildings make is a sense of place. So these communities were built around their old downtowns. And when those got replaced by highway chain properties, that identity also disappeared with them. So by bringing these great buildings back, we also to a really important extent, bring back the identity of these towns. And so it's not only that we've created jobs, but that people are proud to be from these towns. Again, it's given the towns back to the towns

Evan Stern (26:49):

Today. Reservations at La Posada are hard to come by as it is consistently booked at capacity and its success. Inspired Alan to take on the Castaneda making him the owner of both Fred Harvey's first and last Trackside Resorts. They employ over 100 people in both Winslow and Las Vegas. And between them La Fonda and Santa Fe, El Tovar and the buildings at the Grand Canyon, travelers can not only experience the incarnations of Fred Harvey, but trace were the old and modern Wests came to meet.

Stephen Fried (27:21):

This is now living history. You can stay in these four hotels, you learn about the old West and the New West in them, and it's a living thing. It's, you know, and Route 66 is the same thing. The things that it still exist are a way of making the history fascinating, but be to be still alive. Because when you make that drive from the Grand Canyon in Las Vegas, New Mexico, it's still a quintessential American experience that there's no other substitute for.

Evan Stern (27:45):

As for our present history, Stephen comments, there's some irony in the fact that while we can now travel faster than ever, airplanes seem to have regressed to the Pullman days treating people only slightly better than freight. Maybe this is part of why interest in Fred Harvey has surged. So much so, fans have taken to calling themselves Harvey Heads. And if you can believe it, these devotees now even gather each fall for a full on convention at La Fonda where Beverly tells me she and her sister are always given the red carpet treatment.

Beverly Ireland (28:18):

Never thought we'd be on BBC and Good Morning America. And a few things like that and books written about us and people still ask us for our autographs. If you can believe that. <laugh>, We weren't born with a silver spoon in our mouth for sure. You know, we were just, you know, my dad was just a farmer, but we never knew that someday we'd be a part of history and it would follow us the rest of our lives, which has been wonderful in our golden years. You might say,