Postcard from Santa Fe - “El Embrujo de El Farol”

Santa Fe has consistently lured free thinkers and intellectuals of different stripes. People like Georgia O’Keefe. DH Lawrence. And Robert Henri who in 1917 said, “Here painters are treated with that welcome and appreciation that is supposed to exist only in certain places in Europe.” It was around then, on a hill about a mile past the main plaza, a colony of artists began to spring up on Canyon Road. Their imprint remains in the fact that six of its blocks today house over 100 galleries. These spaces are supported by visitors from Aspen and Scottsdale who gladly drop thousands on landscapes before sampling the tasting menus at Geronimo. But on the district’s eastern fringe sits a low slung building of stucco and cedar beams whose walls house an establishment that bridges this district’s well heeled present to its Bohemian past. Its name, as announced by its wooden sign is El Farol. Officially recognized as New Mexico's oldest continuously operating restaurant, we'll learn of its history, but most crucially, through stories, music and an evening of flamenco, get a taste of the place's bewitching atmosphere, or as singer Vicente Griego calls it, "embrujo."

TRANSCRIPT

(As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos, spelling and grammatical errors)

________________________________________________________

Evan Stern: (00:00)

Tennessee Williams once quipped, "America has only three cities. New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. All the rest are Cleveland." Obviously, this is a statement I take issue with, and if there's at least one city in this country that won't get mistaken for Cleveland anytime soon, it's Santa Fe. And while it was bypassed following the Route's realignment in 1937, I don't think any trip along 66 is complete without a stop there. This handsome town of Adobes predates the Mayflower and has born witness to revolts, multiple flags and Wild West shootouts. Yet it's also consistently lured free thinkers and intellectuals of different stripes. People like Georgia O'Keefe, DH Lawrence and Robert Henri, who in 1917 said, "Here, painters are treated with that welcome and appreciation that is supposed to exist only in certain places in Europe." It was around then on a hill about a mile past the main plaza, a colony of artists began to spring up on Canyon Road. Their imprint remains in the fact that six of its blocks today house over 100 galleries. These spaces are supported by visitors from Aspen and Scottsdale, who gladly drop thousands on landscapes before sampling the tasting menus at Geronimo. But on the district's Eastern Fringe. So it's a low slung building of stucco and cedar beams whose walls house an establishment that bridge this district's well healed present to its Bohemian past. Its name as announced by its wooden sign is El Farol. I'm Evan Stern, and this is Vanishing Postcards.

Evan Stern: (01:38)

It’s Friday night at El Farol, and over the bar room’s din of laughter and clinking glasses rises the guitar of Mario Febres. A handsome, sharp featured thirty something of Peruvian descent, he cuts a striking figure, strumming from a chair opposite the hostess stand in an all black, open collared suit. Born in of all places, York, Pennsylvania, he tells me that music brought him to Santa Fe and that flamenco actually wasn’t his first love-

Mario Febres: (03:03)

I actually started out in a punk rock band. And, uh, one of the punk bands that I was listening to had a Spanish type guitar intro. And it got me more curious about flamenco. So then I decided to research more about it. I came out to New Mexico for college to continue studies with different incredible artists that come from Spain and that have been associated with, uh, the National Institute of Flamenco.

Evan Stern: (03:33)

When I hear this, I remark that transitioning from punk to flamenco seems like quite the journey. Then I meet Mario's friend and musical cohort singer, Vicente Griego, who apparently followed a similar road.

Vicente Griego: (03:46)

Uh, I feel like Flamenco found me when I was maybe 20 years old. Um, I'm not one of these people who, whose elementary school went to the Flamenco show and my life was touched and I wanted to be a flamenco artist. In fact, I had just gotten kicked outta my punk band and dumped by my girlfriend. And, um, I I I went to a show before that all happened at the community college in Espanola. And when I heard her sing and I saw the interaction between she and the dancers and my primo playing the guitar, I I knew that I was supposed to be singing as well. I think that flamenco really, besides the fact that it shares some of the defiance with punk rock, uh, you know, kind of like standing up to the mainstream, standing against colonization, resisting all of these changing forces that were imposed upon people. Um, you know, that's, first of all, let me tell you, those are the similarities that it shares with other genres. What makes it really distinct to me is the sense of people in punk rock. Everybody's your people and nobody's your people. But in flamenco the people that you're gonna see me up there with, that's my people right there. And when you sing, you sing for your pueblo. You sing for your family. You sing for the resistance and the survival of your, of your ancestors, of the descendants that are gonna follow. And that's what really makes it distinct to me.

Evan Stern: (05:27)

Decades later, Vicente has more than earned the right to call himself a flamenco singer. A large man whose long dark hair, beard and commanding voice are Shakespearean in presence. He's performed with Jose Greco and appeared on prestigious stages around the world. Yet El Farol remains a personal favorite, and its luminous. Owner Freda Keller Scott tells me of the significance of its name,

Freda Keller Scott: (05:52)

El Farol means lantern or light. And they used to hang a light outside the front door, uh, lantern on when the restaurant was open, and the villagers would know coming back to the plaza that the restaurant was open. And so that's why we always have our lights on.

Evan Stern: (06:10)

A tall, blue eyed Californian with flowing chestnut hair, having put in years as GM, Freda took the reigns of El Farol in 2017. We’re chatting under a fresco in the bar’s earth toned, taverna like front room which The New York Times proclaimed “one of the best on earth.” And while you won’t find fault in their margaritas, sangria or paella, this reputation is owed more to its bewitching atmosphere, or as Vicente calls it, embrujo.

Vicente Griego: (06:39)

There's an embrujo here. And respect that embrujo. Respect those old spirits that are in the walls and in the hands that made the adobe. And so take it slow, take it easy. Don't try to crowd in on something that's not yours. Instead, let it invite you in. And then you enter like a guest and not an intruder. You know what, just driving here, you drive down these ancient streets and those are over walls and they get lit up at Christmas time and you don't know what century you're in. And so just getting here is, is a blessing. And then you walk in the door and you'd feel like if you walked into something that like, you're totally welcome, but, but you're almost not even supposed to be there because you don't want to disturb it, right? And so it's got that vibe of like, there's something sacred here. You know, there's, there's something here that is really different than any other strip mall that you're gonna go, or, or some bar named like Mac and Eddie's or some pool hall, sports bar with a giant TV screen, or, I mean, El Farol is totally, totally different. It's special, but it's also not, it's also not pious. It's wild.

Evan Stern: (07:56)

Recognized as New Mexico's oldest restaurant, having opened in 1835, its rooms are steeped in memories. And longtime former owner David Salazar, tells me of a few of its incarnations.

David Salazar: (08:09)

Yes, it was called La Cantina del Canyon. Uh, and it was the, the, the, the bar of, of Canyon Road. And uh, and it was a place that used to be, that used to sell everything besides booze and, and things of that sort. In the back, in the back there was a, there was a building in the back that used to be a, a barber shop and a they sold grocery store. And it's the place where people that came from downtown Santa Fe as were going into the canyon, to either have a picnic or to have to, to cut wood or to, to go hiking or things of that sort. That's where they stopped and that's where they got their stuff. And, and, and on the way back they stopped and got a drink. And that was in the, uh, in the 1800s. And so, uh, then it got to be a bar in a restaurant, and it was a pretty, uh, uh, uh, quite a bar .

Evan Stern: (09:10)

From what I've heard, the legends of La Cantina are pretty epic as figures like Willa Cather, arts patron Mabel Dodge Lujan, and John Wayne are all said to have spent nights here. And showing me it's famous sunken bar where patrons imbibe from the comfort of straight back chairs, Freda points towards a relic of this saloon's. rough past-

Freda Keller Scott: (09:29)

About three quarters of the way down the bar, there is a bullet hole. And so, I mean, there's lots of stories. Billy the Kid was here. There was the, the history of all the famous people that have come through El Farol has been amazing. But that bullet hole, um, was quite interesting. And there's quite a few stories of how that came about. , I heard that somebody got really mad at the bartender , so maybe he didn't serve him the right drink. I don't know. But, uh, it's a lot of fun. It's definitely wild, wild west and, uh, a lot of fun bar. There used to be, uh, you could go right through the door and horses would go right up to the bar.

Evan Stern: (10:10)

Yet while many original details remain, the white tablecloth dining room signifies that after changing its name to El Farol in the sixties, the restaurant became far more than a rustic dive. And if the space is haunted, I'd wager the spirits of any outlaws are far outnumbered by those of artists whose vibrant, colorful works cover its white stucco walls. Some of these paintings date to the 1940s, but many more were encouraged by Mr. Salazar, who recognized their value,

David Salazar: (10:40)

Proof of the fact that there were bohemians and, and, and, uh, and artists and things of that sort is the fact that, uh, there started to appear on the walls of El Farol, uh, the murals, you know, and they all did it, uh, for the same reason, you know, to pay for their food, to pay for their drink, and to pay for their nights. And, uh, they just happened to be very good artists and came to be very well known. And when I, when I bought it, other artists started coming in and they knew I was receptive to doing that kind of thing. We started adding more things, more things to that Roland Van Loon, who was a Hawaiian young man that came to Santa Fe. Another gentleman that came was, um, Sergio Moyano- an extremely interesting young man born in, uh, in Argentina, in Cordova, in Argentina. So he ended up in, in, uh, in Santa Fe, perhaps drinking a little too much. All of us were. And then he suddenly all of a sudden said, I'm not gonna drink anymore. And he started taking his, his his art more seriously. And we asked him to put some, some murals on, and he went crazy.

Evan Stern: (12:00)

One of the murals Moyano painted features the spirited impressionistic scene of an imagined feria in Sevilla. Guitarists, dancers and women with flowers in their hair clap and sway in motion against an abstract display of yellow and green pigments. This colorful tableau provides a backdrop for the small stage, which each weekend transforms the room into a supper club, showcasing the best flamenco, this side of Spain. This long enduring tradition is what's brought me here tonight and remains one of David's greatest surviving contributions.

David Salazar: (12:34)

It's, it's primal. The, it can be as gut wrenching as anything you've ever heard. Uh, the singers, the dancers, the, uh, the sophistication and yet so earthy. Uh, I remember, uh, uh, seeing people that had never seen flamenco before, see it for the first time were awestruck. They were just, they were just, what? Where have I ever been that I have not heard this? And it didn't matter where they came from, it didn't matter what, uh, what, uh, what background they had. Uh, if it got to you, you felt it.

Evan Stern: (13:16)

David's background is modest, and you could say his beginnings belie the casually confident image he projects. Now in his seventies and short in stature, if not presence, he grew up the son of a shopkeeper in the small town of Hernandez, New Mexico.

David Salazar: (13:31)

The store and the house were attached. And so, uh, it was a general store. We sold everything. Uh, we sold, uh, everything and we delivered all over northern New Mexico and, uh, to different houses and things of that sort. We sold, uh, hundred pound bags of, uh, potatoes and beans and flour and things of that sort. And it was really a general store. We even sold coffins, if you can believe. My father- difficult person to get close to, but he was, he was, uh, his lessons were, were long lasting. He didn't have much education, but he was the smartest man I've ever known. He handled customers well. He treated them well, much better than he did his, his boys . I, we grew up working. I mean, we were open six, seven days a week. And so, uh, the store opened early and closed late.

Evan Stern: (14:31)

This work was so tough as a young man, David says he defiantly told his father he would never own a business. And for many years, that was a promise he kept. After college, he moved to Washington, where he eventually worked as a speech writer during the Carter administration, rubbing elbows with the likes of Cesar Chavez. Yet following the Reagan revolution, Salazar found his way back to Santa Fe where he decided to try his hand at commercial real estate.

David Salazar: (14:59)

So the first listing that I got was for the sale of El Farol. I just couldn't get the people that wanted to buy it, to concentrate and sit down to do the transaction. So, uh, the, the, the, um, I finally said, maybe I should look at it. And so I went to the, to my client and I said, I think I've sold your place and I'm going to buy it. The only thing that was for sale was the business, not the property or the liquor license or anything of that sort. So I insisted, uh, that I have at least an option to buy, to buy the property. And that the, the lady that was the owner of the place said that, uh, uh, we natives of Santa Fe don't sell property. We don't sell land. I said, I understand. And I'm from this part of the country and I know exactly where you're coming from.

David Salazar: (15:58)

And she says, Have you ever been in the restaurant business? And I said, I have never been in the restaurant business. And that was the truth. I had never, never done that. Uh, and so she finally agreed. I think she felt sorry for me. And, uh, and I had a three year option on it. We set the price on everything at that time with an increase in, uh, in the, in the, in the rate of inflation or whatever it is that we set. I can't remember. And with two years and six months, I went up to her house and I said, I'm going to exercise the option. And somebody in that house says, You're an sob, or more explicit. And I said, Thank you very much, and I've got the papers here and we can do it.

Evan Stern: (16:49)

David's career as a realtor proved short lived as El Farol was his first and last listing. At the same time, being new to the business side of hospitality, his early days were not without buyers' remorse.

David Salazar: (17:02)

I remember one time, uh, my mother came up from, from Hernandez and she says, "I want you to meet me at El Farol." And it was Sunday and I hadn't, and I wasn't opening on a Sunday. And I said, "Mom, I don't want to be there. I don't, I don't know what I've done. I've, I've I've messed up." She says, "I want you to be there and come, come up right away." And so she came there and she had the priest from Cristo Rey there. And she says, "I've, I've asked the priest if he would bless the place." And the priest, the priest had apparently told her, "I've never blessed a bar before." , which I thought, of course, but my mom was pretty insistent, and she could get her way sometimes. And sure enough, he went around and he spread holy water all over the place. And I'm doing and stuff, and, uh, maybe it's just in my head, but it started doing better after that. So it worked.

Evan Stern: (18:04)

Following a few early hiccups, he was introduced to New York, tapas chef Denise Dresmond, who revitalized the menu. And it wasn't long before he started hosting entertainment every night. Sometimes there was blues in the bar and dancing on the patio with people like David Byrne and others taking the stage for impromptu jams.

David Salazar: (18:23)

I used to have a, uh, and he's still around, uh, Jerry Carthy- Irish. And uh, he was playing at El Farol. It was a Thursday I remember. And so he was singing stuff like that. And there was, there was a table in the next, in the next room that was right adjacent to the bar. And one of the guys got up and said, and they knew each other from Ireland, things of that sort. And he, and he sang a song with them and things of that sort. And, and so he came back to the table and I heard him say to the table, he says, They don't know who we are. And he says, "Let's, let's knock their socks off." And um, and it was U2.

David Salazar: (19:13)

Way before cell phones. The only phone I had, there was a, and I used to use it as an office phone was a, was a phone booth, was a phone payphone. And, uh, there was a line at the payphone. And soon afterwards, , the place was packed, , things like that.

Evan Stern: (19:33)

But while nights like these proved memorable, the flamenco is what helped cement El Farol's reputation. And Vicente has never forgotten his first night performing here.

Vicente Griego: (19:43)

I came in and I, and I didn't know how to sing a lot of anything. This was maybe 25 years ago, and some singer got sick and they found out that I had been singing. Uh, I somehow got contacted and I showed up and I, I didn't even have the right pair of pants to wear 'em. Well, that became my weekly gig, right off the right out of the shoot. I'd show up on Thursday nights and we'd perform in the bar. And so I I, my first show was, uh, like 1996. And uh, anyway, I find out that the owner of El Farol was my primo David Salazar- distantly, of course. And, uh, so of course we, we had the old school Mafioso connection, like he had to do right by my family. And I had to do right by his, and he had a bottle of eight, um, 18 year old McCallen Scotch.

Vicente Griego: (20:41)

And he said, You want a scotch? I said, I don't even know what a scotch is. Is that what kind of tape? He said, Oh, you gotta learn. He said, There's a bottle and it's not for sale, It's for me, and now it's for you. So every time you're here mijo, I want for you to have a, a drink of scotch and get to know what a good scotch is. He said, What do you normally drink? I was like, um, anything sir. And um, the second he walked away, I realized that that was my bottle of scotch and it was worth, you know, a few hundred bucks to us that's like, might as well be a million dollars. And so I, I unloaded it and gave everybody in the bar a drink until it was finished, because that's what you do and somebody gives you a bottle of scotch, right?

Vicente Griego: (21:25)

And so, you know, because where I'm from and we're here from, I see now we have a dicho- that says one is rich for what you can give, not for what you can have. And so, you know, on that principle, I gave it all away and I had a bunch myself. And, uh, the next week I came in, he said, The bottle's gone. What happened? I said, Well, and he laughed and he said, Okay, new rule. You can't give it away and you can only have five shots a night. Five. And so, yeah, that's my first time singing at El Farol. Some of the wildest nights were when the, when the, I call 'em the Santa Fe Senoritos would show up and they were buzzed and they were feeling groovy. And David would lock the doors and he'd say, Guys, this contract is now between you.

Vicente Griego: (22:24)

Let me know what you need. And we would keep the party going till six in the morning and then maybe into the next day. And then they'd be opening and we'd still have a corner. And that would last for days. And um, I I, that was incredible. I mean, once upon a time in Santa Fe, right? But a nice thing about David is he was a good boxer. I saw guys come in thinking they were gonna come and break into El Farol and David would just stand there and box these guys. And that was crazy too. You know, David was not this giant man, but boy, he was wiry.

Evan Stern: (22:58)

David doesn't dispute this account though. He says sometimes a little moxie was all that was needed to keep things from escalating.

David Salazar: (23:05)

There was a guy that was misbehaving. Big old dude. And if you know me, I'm not big. I'm short. And I'm looking, and I said, I can take care of this because I noticed that there was a friend of mine that was at the door and he was shorter. And I, he's a midget. I went up to him and I said, You and I are going to throw that guy out of here. And so he said, David, you have really lost it this time. And I said, Trust me, we can do this. And so we walked up and I poked, I reached up to hit him in the elbow and I told him that my friend and I were going to escort him out because he was misbehaving and people were not having a good time because of him. So he gets up and he says, Who's gonna do it?

David Salazar: (23:56)

And I said, My friend and I are going to escort you out. So he starts looking around and people edging to the front of their seats and things of that sort cuz they thought they were gonna have to save me and they would've. And so he reads the, the, the offending person reads the situation fairly well. And he took, he, he made the right decision. He says, I've been thrown out of better places and all the cliches that you've ever heard and this and that and the other. So the band stops and we walk out. My co bouncer and I, uh, are making sure he leaves. And so we, we walk back in, thought they were going to see a bloody mess, walk back in. And, and so my friend looks at him and he says, We took care of that, didn't we? And he claps his hands like he's wiping him off. And everybody busted out laughing. And so the good and the bad and, uh, all of them, all of 'em were, were, were in the end good.

Evan Stern: (24:57)

Be that as it may, good times can be exhausting. And after 32 years, David shocked Santa Fe in 2017 when he announced he'd be turning El Farol's keys over to Freda and some new investors. But retirement isn't something Mr. Salazar does well and you can find him now holding court at the Primo Cigar Shop- a humidor and lounge he bought two years ago where visitors can still experience his hospitality accompanied by fine tobacco.

David Salazar: (25:25)

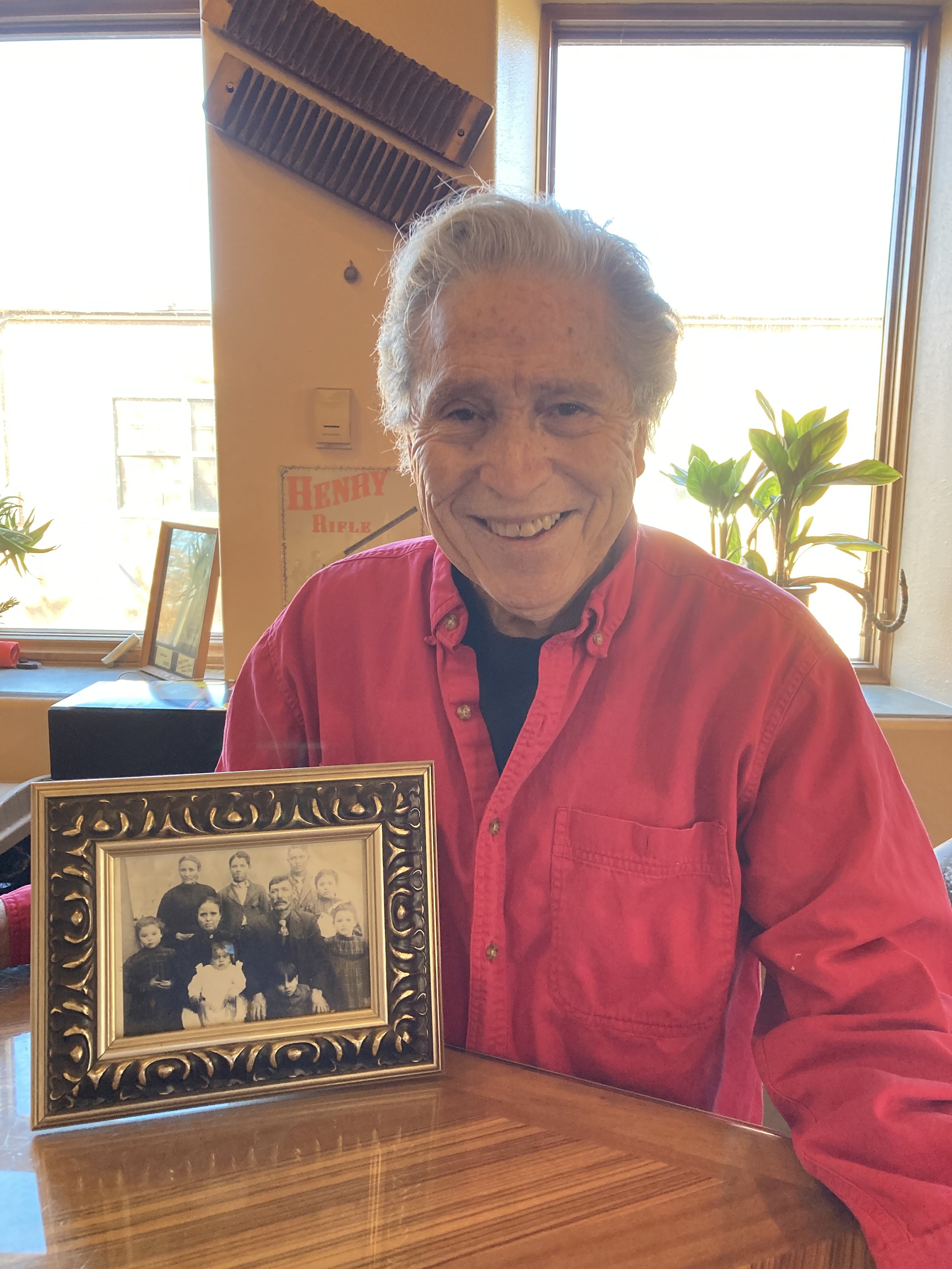

Uh, I had to do something and I had to be, and I might as well be a part of this as as anything else because I used to come here often. It also has a place where a lot of people come and sit down and discuss and, and opine about different kind of different kind of things, whether it's religion or politics or, or or anything else. And same kind of arguments, the same kind of, uh, debate, the same kind of, uh, passion. Uh, and so, uh, uh, I'm glad I got here because what would I be doing at home? I've always had a photograph that I, that I, that I have had at every one of my jobs and businesses. And it is my grandfather and his family and my grandmother on my father's side when my father was just in that photograph. He's just six years old. And uh, they're the ones that have given me strength cuz they look as old world as you can possibly get. And they were dressed in their very best. And um, and it's something that would always be with me. Sorry,

Evan Stern: (26:40)

As for El Farol. While on the surface, Freda bears little resemblance to her mentor David, having worked here for the better part of a decade, she understands this place's aura. And as I sip rioja while Mario, Vicente and a trio of dancers take the stage, I'm enveloped by the famous embrujo I was warned of.

Evan Stern: (27:23)

Martha Graham once said, "The body says what words cannot." And attempting to describe the intense passion and intimacy of tonight's show would be a foolish exercise. What I will say is that when at a great performance you enter a state of hypnosis. More than forcing me into the present, like stepping on a magic carpet, I feel this music rapidly pounding feet artwork and paella transports me elsewhere. Maybe a fantasy version of Andalucia. Then I realize that elsewhere just happens to be El Farol, and I hope its lantern continues to shine its beacon on Canyon Road for years to come.