Episode 1 - Postcard from West Austin, “Drinking at the Dry Creek”

A beer will only cost you $3 at Austin’s Dry Creek Cafe. What’s more, at the time of our visit their bartender, Angel, was only the third to work here since 1953. We’ll swap stories with her over a cold one, learn about the cedar choppers who once drank here from author Ken Roberts, and hear Bobby Earl Smith perform the murderous ballad this salty joint inspired. We’ll also talk about the infamous Sarah, who was named in her obituary “the meanest bartender in Austin,” and explore the nearly seven decades of history this hidden dive, now surrounded by mansions has borne witness to.

________________

Interested in visiting The Dry Creek? For more info, check them out on facebook or Instagram

To learn more about cedar choppers, see pictures and order Ken Roberts’ book, visit - thecedarchoppers.com

To listen to and experience the remarkable music of Bobby Earl Smith, head over to- bobbyearlsmithmusic.com

TRANSCRIPT

(Please note- As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos.)

Evan (00:03):

But, I mean, yeah. Can you tell me a little bit about what Austin was like when you first got here?

Angel (00:07):

Oh, it was cool. It was small. It was friendly. Wasn't hardly any traffic. It was AFFORDABLE.

Evan (00:17):

I'm one of a proud few who can claim to have been born, bred and buttered in the city of Austin, Texas. My Dad will tell you, I popped my first tooth on an empty bottle of Shiner at the Armadillo Christmas Bazaar, so I like to think my local cred is pretty legit. I love this city. Unabashedly. But it also frustrates me in ways that only a native can appreciate. It's more than tripled in size since I was born, and the laid back college town my parents fell in love with no longer exists. Some say old Austin died when Las Manitas, a beloved Mexican spot downtown, was forced out by a Marriott. Others say it happened long before in 1981, when the famed Armadillo world headquarters was torn down. But I know of at least one hidden, oft forgotten spot where the spirit of old Austin still lives- And today invite you to join me for a cold one at the Dry Creek Cafe where we'll swap stories, songs, and even a little history with some of those who've gathered here for decades. I'm Evan stern, and this is Vanishing Postcards.

Evan (01:34):

Juke boxes aren't what they used to be. Don't get me wrong. I love that we live in a day and age where we can indulge in whatever guilty pleasures we're feeling thanks to YouTube and Spotify. All the same. I think we lost something over the last 10 years when jukeboxes started to go online. The choices are limitless and in some places you can even pull up whatever song you feel the entire bar should hear from the convenience of your phone. But call me old fashioned, there's some establishments where people just shouldn't be allowed to play Taylor Swift. Well, you don't have to worry about that at the dry Creek cause they didn't even make the switch over from records to CDs.

Angel (02:17):

It's the last 45 record jukebox in a bar in Austin. Uh, the same stuff. Most of it that's been on there 40 50 plus years. It's only when it starts getting to that ch-ch-ch-ch stage, that it gets replaced with something else.

Evan (02:36):

That's Angel. Short. Stout. 68 years old with thick glasses and a bob of graying hair. She's only the third full-time bartender to rule this roost since Sarah, the bar's departed an infamous second owner bought the place back in 1953. Housed in a two-story shingled shack with chipping yellow trim and a tree shrouded deck that once overlooked the edge of Lake Austin, it sits at the Northern foot of Mount Bonnell and doesn't look much different than it did when it opened roughly 70 years ago. In fact, the sign still advertises it as a boat dock and cafe, even though they don't serve food or have a dock-

Angel (03:15):

Well, there is still a dock down there, but it's been decades since they sold the property next door that had a road that went down to the boat dock. It used to be- I think they even rented boats and stuff like that at one time. Now it's private. As far as the food- under the hood over there, there used to be an old stove where Sarah cooked hamburgers when she felt like it. And you ate them how she fixed them. And liked them. A real laid back dive. We don't give a flying flip for most of your regular bar types. We don't like change here!

Evan (04:02):

However, while beer will still only run you $3 change has no doubt surrounded the dry Creek. If you walk a few yards from the gravel parking lot, you'll happen upon an imposing secure gate leading to a row of multi-million dollar waterfront mansions. What had remained country into the early nineties now ranks among the priciest zip codes in all of Texas. And when mentioning the dry Creek to someone who remembers this town long before it became a thing, chances are they'll ask that place is still open. Then they'll start talking about Sarah

Ken Roberts (04:38):

Remarkable woman named Sarah who even then look absolutely ancient. I don't know. She was probably in her forties, you know, but we were young and- Irascible. Would give everybody shit all the time. You know, it was just an, uh, a legend that she became a true legend. I don't know what happened to her.

Bobby Earl Smith (04:58):

You never knew when Sarah was going to open. She opened whenever she well pleased. And so sometimes you'd go and she wouldn't be open. Uh, Sarah was, she was just a little thing. And you could kinda tell the weather from the expression on her face. You could recognize if you had a half a lick of sense when to engage her and when to just to order your beer and leave her alone.

Angel (05:22):

Oh, I loved Sarah. She was a cantankerous, ornery, great, wonderful woman. Gave people all kinds of shit. But she liked me. For some reason. She didn't seem to like many women.

Evan (05:39):

What do you think it was about you that she liked?

Angel (05:42):

Hard to tell. Maybe I was just as contrarian as she was,

Bobby Earl Smith (05:47):

I mean, she was just good grief. She was out there amongst all those Cedar choppers. She had to take care of herself and she didn't take any guff from anybody. Sarah was just Sarah. You know, she was wonderful. I loved her.

Evan (06:02):

That's a sentiment shared by Sarah's son, Buddy Jay Reynolds, a retired mining engineer and former state rep who helped save the bar in 1984 and has remained a quiet owner ever since. You can count on finding him there most Tuesdays and Wednesdays, when he drives in from Lexington to watch Wheel of Fortune with a group of regulars. Tall and affable with a well trimmed beard, he cuts a striking figure that belies his 82 years. Sitting in a chair, outside the bar's entrance, smoking a cigarette and nursing a long neck, he openly shares with me details of his mother's biography.

Buddy (06:38):

My mom was a one of 10 kids and they all grew up in Lexington and uh, her dad got killed. And uh, but I'm trying to think, I don't know what the year it would have been probably around- He got killed in 1926 and mom took care of the remaining kids. And uh, and she went through a couple of marriages. At that time, there was nothing out here. Most of her business was Cedar chopper. In fact, they were still cutting cedar on this. They had just finished up- all of this was cedar. So she claims that's why her language was always so colorful because that's the way you had talked to cedar choppers. You know, they cut it all with the axes. So these guys were stronger than oxes. They partied. She would, this place would be on a Friday, Saturday, it'd be steady. Room only was cedar choppers. Yeah.

Evan (07:42):

If you've never heard of cedar choppers, you could be forgiven as they become something of a forgotten subculture in central Texas. The cedars are still around responsible for making Austin and its surroundings notorious for allergy sufferers. But back in the day, a decent living could be made clearing ranch land and reselling timber for posts. And the folks engaged in this business were a tough and insular crowd to say the least. To learn more about them, I sat down with Ken Roberts author of the engaging and exhaustively researched book, The Cedar Choppers on the Edge of Nothing.

Ken Roberts (08:18):

They were Appalachian hillbillies transplanted right here. And the amazing thing of course, is that rather than being in like West Virginia and have the nearest city be Washington DC, they're butted right up against Austin and San Marcos and San Antonio. So they're just butted right up against quote civilization. If you think Scots-Irish think Braveheart, you know, these are, these are people who were always pushed around first by the English then the English, move them over to Ireland. Then they got pushed out of Ireland. They came over to, you know, they weren't welcome anywhere in the United States. They were always violent. And the homicide rate in Appalachia during, at the turn of the century, exceeds the homicide rate of any country in the world today, including Honduras, some of the most violent countries there are. So that's how they settled issues.

Evan (09:13):

Ken, who grew up a child of means on Austin's West side in the 1950s, came dangerously close to getting a taste of this vengeance in his first encounter with some kids from the other side of the Lake. He and a friend had ridden their bicycles to cast a few lines over the low water bridge at Tom Miller dam when their fishing expedition took a sudden turn.

Ken Roberts (09:32):

And so, um, we're going down fishing and me and a friend named Dudley we're on our bicycles when we got off our bikes and are walking to where we were going to fish. And these three kids show up, um, and they were really different looking than us. They were smaller, but they were kind of skinny and scrawny and really tan and barefooted. And, you know, uh, looked really hard, just looked, you know, there was nothing soft about them. And one of them held up a stringer of fish and they said, "You want to buy some fish?" But Dudley, my friend, he turned out to be sort of a, a bad boy, uh, later on in life. And he said, "If we wanted to buy fish, we'd go to the HEB," which is the name of a famous grocery store in Texas. And these kids looked at him and turned around and walked away. And I think I said something like "Dudley, I really don't think he should have said that to those boys." And sure enough, they were back in about five minutes and one of them had a club, you know,. And it was just apparent to me, even though Dudley was strong and we were a bigger and stuff that these guys weren't going to quit. They were, they were really, they were really off

Evan (10:39):

Needless to say, the chopper families who lived within a stone's throw of Austin were famously rowdy. And the crew that inhabited the land near the Dry Creek ranked amongst the roughest of them all.

Ken Roberts (10:51):

You get to Dry Creek, you better turn around. And if you happen to get to Bull Creek, you better just go home. I mean, that's, you don't want to be there. It's dangerous. Because again, you're there saying, what are you doing here? One sheriff, he's the deputy sheriff. He wanted very badly to make a name for himself and become sheriff. And, and he figured the way to do that is by busting one of, some of the more prominent cedar choppers. And one of them was named Dick Boatwright. He was kind of the leader of the Bull Creek clan. And it was a number of families, all living in Bull Creek, very intermarried. Um, and so he went out there and, um, he could only drive so far- a big rock had fallen in the road. And so he was walking along and there were, he said, there was this kid there sunning himself. Well, I sort of seriously doubt that part of the story. The kid was probably there literally as a lookout of some sort, uh, and about 11 years old, 12 years old. And he asked, uh, the kid, he says, "Do you know Dick Boatgwright?" Kid says, "Yep. I know him." He says, "Well, you know where he lives?" "Yep. I know where he lives." Not giving a whole lot of answers. Right? Very typical, not, not very talkative. He said, "Well, will you take me there?" Kid says, "Yep. For a dollar." He says, "Okay, you take me up there and we get back here, I'll give you a dollar." Kid says, "You ain't coming back!"

Evan (12:19):

But by the sixties, as chainsaws replaced, double bladed, axes and ranchers found steel posts more efficient than cedar for stringing wire, the industry, and those who worked at began to fade from the Hills and Sarah found herself serving beer to a very different crowd.

Bobby Earl Smith (12:45):

Sings....

Evan (12:52):

Bobby Earl Smith moved to Austin from San Angelo in 1965 for law school and discovered the dry Creek along with his fellow hippy crew, sometime around 1967,

Bobby Earl Smith (13:03):

I would, you know, days when I should have been going to law school or at the library, I'd often be up, up at the Dry Creek. I kind of liked to go on overcast and cloudy days and um, go up and play that jukebox box. And I would play Marty Robbins. Uh, and I loved to go play the jukebox out there. And, um, like I say, on those kind of blue days, this one, and then nobody would be there cause they wanted to come when the weather was better. So a lot of times there would just be me and maybe one or two other people there. And those kinds of days,

Evan (13:52):

By the time Bobby passed the bar in late 1970, he was working as a musician full time and put his legal career on ice for 14 years. One night, while playing a gig in a chance encounter, he'd meet a long, tall Cajun woman by the name of Marcia Ball. And within two weeks, they team up to form a group called Freda and the Fire Dogs. Pioneers of what some might now call alt-country, they were soon in talks with Atlantic's Jerry Wexler and recording. Around this time, inspired by the Kingston Trio's, Tom Dooley, Bobby sat down to write a murder ballad of his own and sent it over to his pianist friend, Ron Howard, for an arrangement. The story of a man who stops a woman in a lover's quarrel, its setting was... familiar

Speaker 3 (14:37):

Sings The Dry Creek Inn.

Evan (15:26):

Did You ever play the song for Sarah?

Bobby Earl Smith (15:30):

That's a good question. I'm not, no, I never sat down and said, Hey, Sarah- Looking back, It would have been good idea if I'd have given her a heads up. I think she actually put it on the jukebox if I'm remembering correctly and then took it off at some point, when somebody realized, when she realized what it said... If it hadn't been for Sarah, they had caught me, but she took me and she hid me. She cooked for me and she did me. And uh, I mean I ran with it. Did rhymed with hid. And uh, but I guess at some point she figured that out and she did not like it. And so she was threatening to shoot my ass. Alvin Crow told me, he said "Sarah's going to shoot your. If you come back out there. And I said, "Oh, she's not gonna do that." And he said, "Yes, she will."

Evan (16:48):

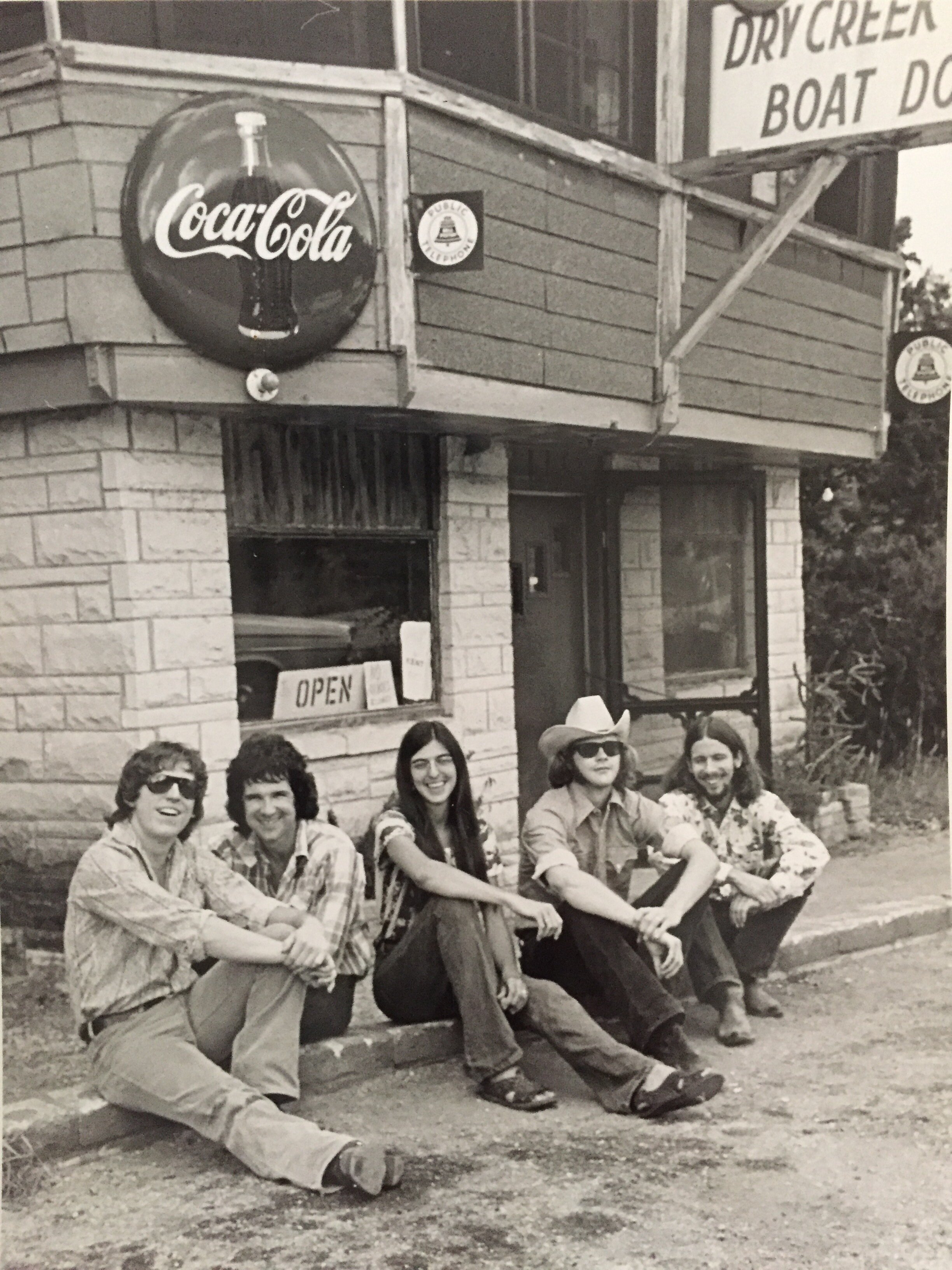

He then tempted fate by one day, attempting to stage a photo shoot outside the cafe.

Bobby Earl Smith (16:53):

I said, let's go take some pictures. Uh, it would have been for this cover. We'd no more than gotten there. And I was standing in the road in front of the Dry Creek and all of a sudden the door comes open. There was a screen door on the outside and I couldn't really see, but I could hear the voice. I knew who it was. And I heard this voice say, "Bobby Smith! I know what you're doing. Get your ass out of here!" And I went. "Let's go!" You know, I'm not stupid. I'm not going to hang around with Sarah if not wanted, you know. I didn't, I didn't think she'd shoot me, but I didn't want to run the risk. So we piled in the car and beat feet back out of there.

Evan (17:35):

I do suppose though, that Bobby can take some solace in the fact that he was in good company, as Sarah once directed her wrath at none other than Willie Nelson

Angel (17:43):

I've heard tell it was, uh, she told him, he was playing his guitar in here bothering

Angel (17:50):

folks. She told him to go put it in his vehicle. When he told her, it didn't lock, she told him, "Well, then you might best go along with it. Others say that he was smoking pot upstairs. And that pissed her off. So, who knows?

Evan (18:09):

I have my own Sarah story, too. It's far less epic than any of these, but is maybe a little surprising. My mom and dad brought me here a couple of times when I was probably five or six. It wasn't a frequent stop, but I do remember Sarah. She did look ancient. But I swear, after she opened my bottle of orange crush, she actually smiled at me. When I tell this to Angel, she says "You're full of shit," but Buddy, isn't surprised. He's quick to tell me that his mom wasn't all salt and vinegar. He stresses that she never laid a hand on him. Never would have. That she taught him independence and cared deeply for the disabled.

Buddy (18:59):

She was always, you know, if, if somebody was sick, she was there. Yeah. She always had this big heart for anybody that needed help. Yeah.

Evan (19:09):

Sarah ran the place and worked the bar pretty much on her own until age 91 and died about a week shy of her 96th birthday back in 2009. But Angel will tell you she still haunts the place and has considered summoning her a few times when dealing with rowdy patrons.

Angel (19:24):

Oh, I've threatened them with her on occasion. I let quite a few know that she still haunts the place. Oh, she messes with lights, especially with the clock up front. It can, I've seen it spin around like it was fricking possessed.

Evan (19:42):

In many ways, I think Sarah's spirit is certainly a big part of what's keeping this place going. And that's something that buddy will admit to -

Buddy (19:50):

Not, uh, we're not, we're not getting rich on it yet, but we, I keep it open in memory of my mom. Yeah.

Evan (20:00):

But while I trust that Buddy has inherited some strong genes from his mother and appears to be in great shape, the fact is, he is in his eighties. So what happens when he too is gone?

Buddy (20:13):

It goes to my kids. Yeah. Yeah. I'm hoping they'll operate it. If they don't, they could sell it. Yeah, no, it's an acre and a half here. So if they don't want it- sell it, yeah. I'm not going to worry about it. Yeah.

Evan (20:29):

Although the Dry Creek for now is under a steady hand, each time I come here, a part of me can't help but wonder how many visits I have left. Vox reporter Alissa Wilkinson wrote that a great bar is "A third place. An in-between space where time seems to pause. On the best of nights, a great bar, feels like a glimpse of heaven. On most nights, it's where you go to escape the world outside for a while." Time does pause at the Dry Creek, but a late afternoon on the weathered upstairs deck isn't just an escape from the new Austin. It's a retreat to the old. And what do we lose when this place inevitably serves its final Bud?

Bobby Earl Smith (21:11):

But for some reason, Dry Creek the building, Sarah, the, the, the post oak trees, the, the Hill around it, it all- There was, there's a sense of place. That's magic. You know, I remember reading, I think in a J Frank Dobie book about Bigfoot Wallace, uh, scouting through that area and hunting through that area and living in the wild out there in a cave. And it just has that, it, it feels like something happened there. Something, not necessarily grand, but something that is special. Something happened there. It just feels that way. To me, it feels like things happen there. That things still happen there. There's an ongoing river of something about some places. And that's how I feel about The Dry Creek. There will be some thing missing that leaves a hurt in my heart. Um.... But hell, it's still there today and you can get $3 beers. So, what's not to like?!

Evan (22:49):

Absolutely. I think that's, uh, you know, I could ask more. I could say more, but I think that's a good place to maybe end. Right.