Postcard from Tulsa - “The Ghosts of Greenwood”

In 1921, the city of Tulsa bore witness to the greatest incident of racial violence in American history, when the prosperous African-American neighborhood of Greenwood was invaded and destroyed in an act of mob terrorism. But while this disgrace which resulted in as many as 300 deaths was ignored for decades, a century later, it seems to be getting its share of attention. Last year, 107 year old survivor Viola Fletcher, riveted Congress with her eyewitness testimony in a public plea for justice, while the president visited Tulsa to commemorate its Centennial in a display of apology. Memorial banners were unfurled downtown and walking this city's streets you'll happen upon murals, statues, parks, and even a 30 million dollar museum built in remembrance. But what happened to Greenwood after 1921 and what can be found visiting the neighborhood today? Join us as we walk its streets, and hear from locals and historians who are striving to tell this district’s full story.

TRANSCRIPT

(As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos, spelling and grammatical errors)

________________________________________________________

Evan Stern (00:00):

Michael Wallis will proudly tell you he's lived in seven of the eight states Route 66 cuts through and has called Tulsa home now for 40 years. He and his wife, Suzanne moved here in '82 thinking they'd bide some time before settling in Santa Fe, but like Cyrus Avery, they've adopted this city as their own and are quick to praise the beauty of the Arkansas River and downtown's Art Deco skyline. At the same time, they're clear eyed about Tulsa's challenges, failures, and dark history, which is a nerve Michael hit on during his first extended visit in 1980-

Speaker 2 (00:37):

I asked our host the chamber commerce- Can you get me some old newspaper reporters who were active in the twenties and thirties here? And they said, well, there's still some around. So they got me about eight or nine. Of course they were all men. White. And we met in a conference room in the Mayo Hotel. So we talked about territorial days, and statehood in 1907. We talked about the, how it evolved into cow town, Tulsa town and, and had a good conversation. And then I said, "Well, let's talk about, uh, let's talk about May 31st, 1921." And, uh, and so when I brought that date up, I immediately saw these faces change and I saw them go white knuckled on their chair and furrow their brows, and one old guy says to me, "We don't talk about that." I said, oh, he said, "No, we don't talk about that." He said, "That was in the past." And I said, "Everything we've talked about today is in the past long before 1921," he said, "Nobody talks about it." And then one guy said, "Why would you even bring that up?" And I said, "Exactly, because of the way you're reacting." I said, "You all are denying your history. Aren't you?" And boy, did they get pissed. And I didn't care.

Evan Stern (02:12):

The incident of which these men refused to speak was of course, the Tulsa Race Massacre, which is regarded today as the single worst incident of racial violence in American history. But while this disgrace, which resulted in as many as 300 deaths was ignored for decades, a century later, it seems to be getting its share of attention. Last year, 107 year old survivor Viola Fletcher, riveted Congress with her eyewitness testimony in a public plea for justice, while the president visited Tulsa to commemorate its Centennial in a display of apology. Memorial banners were unfurled downtown and walking this city's streets you'll happen upon murals, statues, parks, and even a 30 million dollar museum built in remembrance. But what happened to Greenwood after 1921 and what can be found visiting the neighborhood today? I'm Evan stern and this is Vanishing Postcards.

Terry Baccus (03:41):

Well, I grew up here in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It, it was wonderful. It growing, I, we, we was, we raised middle class. The Oklahoma Eagle was the black owned newspaper. One of the largest black owned newspapers in the state and in the United States. At the time I can remember at eight year old, eight years old, um, walking to Greenwood to get the Oklahoma Eagle, to come back out and sell the Eagle. I would see remnants of what took place on Greenwood that just drove me. And so, uh, I just, I love Greenwood. That was my love for Greenwood.

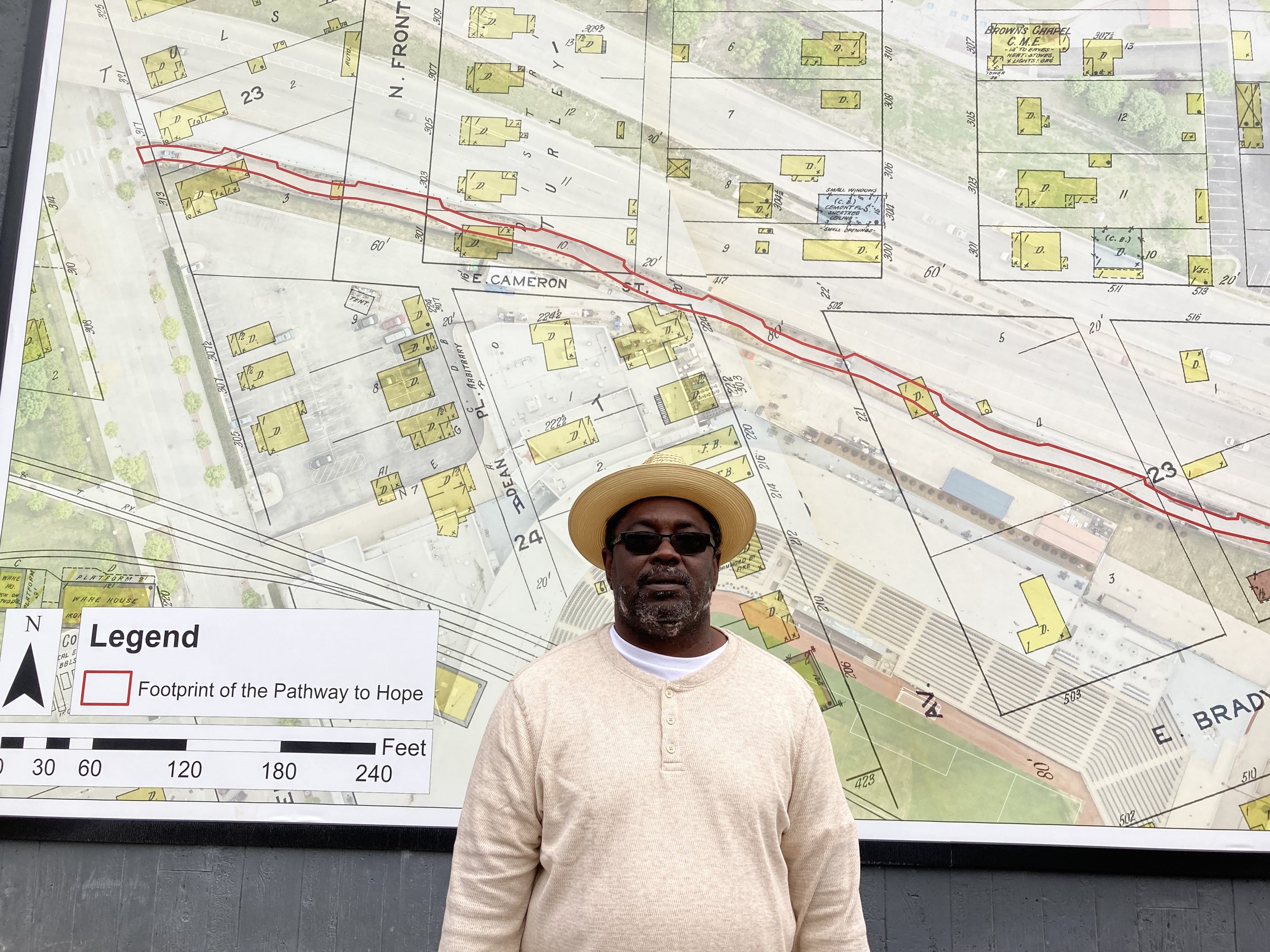

Evan Stern (04:16):

Hang around Tulsa with Terry Baccus. And you might hear a passerby or two call out to him as the mayor of Greenwood. A large man with a graying beard, shades and fondness for straw fedoras, he's a member of the Muskogee Creek Nation and tells me his parents hailed from two of Oklahoma's oldest surviving black townships. His roots here run deep and Tulsa is no doubt home, but home can often be a complex place.

Terry Baccus (04:46):

I mean the narrative of the city of Tulsa and the whole, excuse me, is a, a great place to come. A great place to, you know, raise a family, which it is. It's a great place. You know, I'm not going to take from it, but, uh, there's another side, you know, the trauma to it. I mean, and it's even, it just, it, it is bred in us in the community, whether we want to accept it or not, you know, and some of us don't accept it, but it's still there. The trauma is still there.

Evan Stern (05:22):

The origins and continued cycles of this trauma is something he takes pains to explore and share with visitors, through the tours he guides around Greenwood today,

Terry Baccus (05:30):

Greenwood is not imaginary. You know what I'm saying? It's it's alive. It's living. It's something that took place. It's something that will always be spoken about through generations. I want the people to know that, you know, they lived there. They really lived. When I'm giving tours, I'm teaching right about history. I'm teaching about something that happened to a people that, that lost everything. You know, I'm, I'm teaching about something about a people who was resilient enough to build back up again.

Evan Stern (06:00):

Indeed, it's important to stress that Greenwood did rebuild and lived to prosper again. Terry and most everyone I speak with are United in their belief that this neighborhood story is ultimately one of resilience and self determination. But the ghosts of 1921 persist, and while Greenwood's geographical lines remain, all but a few of its 35 blocks of homes and businesses were demolished to make way for freeways and OSU's campus in the name of urban renewal. Knowing that 10 to 12,000 lived here into the sixties, seeing its state today is a jolt to the system and hearing Phil Armstrong, the Ohio born director of the new Greenwood Rising History Center speak of his first visit. I can relate.

Phil Armstrong (06:48):

It was, it was, uh, shocking to, to, I guess that's the best word to say, you know, you, you hear about it, you read about it and then you get here and you're, and it's it's, it was kind of a disappointment that this is all that was left, uh, that it was, you know, a half a block of two historic buildings on each side of the street, uh, that you can pretty much walk in less than five minutes. And that's what remained. Uh, and then you see this vast open area and these fields, uh, literally, you know, fields and, and the stairs to nowhere where homes used to be. And, and it was a, it was just, uh, as the, as the, as the raw statement says, it was like a punch in the gut. Like, wow, you know, everything that I read and everything I heard about how incredible this community was for black Americans, and this is what it's come down to. Uh, it was, uh, it was, it was sad. It was exciting to be here with my friend, but it was sad to see that this is all that was here.

Evan Stern (07:48):

So what was Greenwood? Walking me through a hallway in a community center whose corridor provides a timeline of exhibits surrounding the neighborhood's history. Terry gives some context for the economy that helped fuel its ascendence.

Terry Baccus (08:02):

You've heard of Dubai, right? So Dubai was famous for oil, right. So in the early 19oos, so was Tulsa. Tulsa was Dubai, right? So all the giants came out here, you know, the Rockefellers. And so, uh, that oil was the main reason that that prosperity thrived in Tulsa and Greenwood in itself. Right? And so the money trickled down, right?

Evan Stern (08:30):

But more than this, Hannibal B Johnson who serves as Greenwood Rising's curator stresses that Greenwood was a community born of necessity.

Hannibal B Johnson (08:39):

It would not have existed. Had it not been for Jim Crow segregation. So in essence, the people in the Greenwood community, the black community faced an economic detour. If you can metaphorically see them approaching the gates of economic opportunity in downtown Tulsa and white Tulsa establishment, Tulsa and being turned away, turned away back into their own environs, their own geographic area, where they created this robust economic community where dollars circulated, because they were constrained by segregation-

Evan Stern (09:15):

Between this segregated ecosystem and inflow of wealth from Tulsa's booming industrial economy, Greenwood provided fertile ground for black entrepreneurship. Its father was OW Gurley who in 1899 bought the district's initial 40 acres for development. By '21, he owned a portfolio of over 100 properties while his frequent partner JB Stradford opened a luxury 54 room hotel. John and Loula Williams built the elegant Dreamland Theater and Simon Barry's jitney company proved so successful, he even bought a plane that serviced Oklahoma's rich oil barons. Such acumen, coupled with the community's many doctors, lawyers, teachers, and professionals inspired Booker T Washington to proclaim Greenwood Black Wall Street. Yet this advancement coincided with the release of Birth of a Nation, the refounding of the KU Klux Klan and 1919's Red Summer in which over three dozen American cities bore witness to lynchings, anti-black riots and other acts of white terrorism. These simmering racial resentments came to fester in Tulsa as well and soon reached a terrifying boil that Dr. Scott Elsworth, author of Death in a Promised Land describes-

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (10:36):

On Memorial day, Monday, May 30th, 1921, a 19 year old shoe shiner named Dick Rowland- Dick worked at a, at a white owned and white patronized shoe shine parlor, but there were no bathroom facilities for the African American shoe shiners. So the owner had arranged for the shiners to go down the block down Main Street to ride an elevator in the Drexel building to the top floor where there was a quote colored bathroom. Um, we know that, uh, he enters the, uh, elevator and the operator in the name of the Drexel building was a 17 year old white teenager named Sarah Page. We think what happened is that he tripped as he was entering, stuck out his hands to break his fall, probably caught Sarah on the shoulder. She was startled, let out scream. And he takes off. Um, a clerk in the Drexel building, a white clerk,

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (11:31):

hears the, the, the scream, runs out in the hallway, sees Dick running away. And so the police are summoned, but, uh, they don't put out an all points bulletin or anything like that. The next morning they do go and arrest Dick Rowland. They take him to the courthouse downtown, put him in a jail cell on the top floor. Um, Sarah Page will refuse to, to, uh, to press charges. Dick Rowland will ultimately be exonerated, but that afternoon, a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune catches wind of this. There's a front page article that is this fantastic writeup of the event in the, in the, uh, Drexel building. And that he'd gone into the elevator, scratched her face, tore clothes, and obviously tried to rape her. So the Tribune hits the streets at 3:30, by four o'clock there's lynch talk on the streets of downtown Tulsa, which soon turns into action. Gathering outside the courthouse are 100, 200, 300 white people as every hour goes by. While this is going on,

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (12:35):

word, meanwhile hits Greenwood. And then finally at about 7:30, a group of 25 black veterans, all of whom are now armed with pistols rifles and shotguns present themselves to the sheriff saying, we're here to help you protect the prisoner. If you want us, the sheriff says, get the hell outta here. Uh, the men leave, but they're presence absolutely enrages and electrifies the white Lynch mob. Uh, members of the mob now go home to get their own guns, to bring their neighbors down. And you know, the, the city, the mob grows as the hours go 600, 700, 800, 900 a thousand people. Finally at about 9:30, there's a second visit of African American veterans and other men. Uh, this time 75 in number. An elderly white man goes to up to a tall black vet who had fought in France and says, "Where you going with that gun?"

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (13:34):

And the vet says, "Well, I'm going to use it if I need to." White man says "Like, hell you are. Give it to me." A struggle ensues, a shot goes off. The police now suddenly show up, but rather than disarming the lynch mob, they, uh, they start deputizing members of the mob as special deputies telling them to get a gun and get a Negro. Shortly before dawn on the morning of June 1st, uh, 16 year old Bill Williams is in his family's apartment on the second floor of the Williams building right at the corner of Greenwood and Archer. And Bill told me in 1975 that he looked across the railroad tracks towards the white part of town. And he said, it looked like the Milky Way. And all these little dots of lights were the lit cigarettes and cigars and pipes of thousands of armed whites who were getting ready to invade

Evan Stern (14:27):

Invade they did. And while black residents fought back valiantly, being grossly outnumbered against a mob that had in some cases even procured machine guns, their efforts proved doomed. Many accounts even report that dynamite was dropped on Greenwood from planes, making Tulsa the first American city to be bombed from the air. Recounting this trauma, one anonymous victim wrote the following-

Witness 1 (14:56):

After they had the homes vacated, one bunch of whites would come in and loot. Even women with shopping bags would come in, open drawers, take every kind of finery from clothing to silverware and jewelry. Men were carrying out the furniture cursing as they did so saying "These Negroes have better things than lots of white people." I stayed until my home was caught on fire. Then I ran to the hillside where there were throngs of white people, women, men, and children, even babies watching and taking snapshots of the proceedings of the mob. Some remarked that "the city ought to be sued for selling niggers property so close to the city." I watched this awful destruction from where I sat on the hillside. As I sat watching my modern 10 room and basement home burn to ashes, an old white man came by. Addressing me as "Auntie" he said, "It's awful. Ain't it?" And offered me a dollar to buy my dinner with.

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (16:07):

By the time state troops arrive from Oklahoma City in the middle of the morning on June 1st, uh, Greenwood is gone. 1100 black owned businesses and homes have been destroyed, looted and destroyed 12 churches, 25, you know, meat markets and grocery stores, 30 restaurants, doctors' offices, two theaters, um, uh, a, a, a hospital, uh, uh, one of the two schools, uh, uh, a, a post office, a library branch, everything is gone. It's, uh, you could never find for years and years, you could never find photographs of Greenwood after the massacre. You can find them today. And if you look at 'em, they'll look like Hiroshima or Nagasaki

Evan Stern (16:53):

In the wake of this assault, many, including OW Hurley himself fled to never return yet many more stayed to rebuild. This resolve is evident in a letter, a man sent a friend in response to his receipt of $40 and an urgent plea to move to Detroit.

Witness 2 (17:12):

Dear Curtis, It is just like you to be helpful to others in times of stress like this. We are facing a terrible situation. It is equally true that they have destroyed our homes. They have wrecked our schools. They've reduced our churches to ashes, and they have murdered our people, Curtis. But they have not touched our spirit. And while I speak only for myself, let it be said that I came here and built my fortune with that spirit. I shall reconstruct it here with that spirit and I expect to live on and die here with it. Oliver.

Hannibal B Johnson (18:01):

The, the overarching narrative here for me is the indomitable human spirit. It it's the fact that the community was decimated in 1921, but rebuilt, um, really quickly after the devastation. I tell, tell people that the, the rebuilding began even as the embers from the massacre still smoldered. And by 1925, this community hosted the national conference of the national Negro business league, which is Booker T Washington's black chamber of commerce. The peak of the community as an economic and entrepreneur entrepreneurial community is in the early to mid 1940s. Ironically, one of the things that happens in the sixties and seventies and so forth is integration because integration then allows those dollars that had previously been circulating by design and by necessity within the community to outflow and dollars were not flowing in from the white community into the supply community. So it undermined the financial foundation of the community, which led to business failures

Phil Armstrong (19:02):

and so forth. Blight. Blight then gets the attention of urban renewal, which is if, if you look at it from a benign perspective is designed to eliminate blight and create beauty in communities and so forth. Unfortunately, the blight, not just here, but elsewhere existed, largely in communities of color, largely in voiceless communities, unrepresented communities, communities that could not resist when the urban renewal authority came to seize properties for just compensation, I'm doing air quotes around "just compensation." So it's the combination of integration and urban renewal. Um, coupled with a couple of other factors like the changing economy, more generally, it's those factors in combination that led to where we are today in the Greenwood district.

Evan Stern (19:55):

So where is Greenwood today? As Phil mentioned as a commercial district, it's essentially become limited to one block. And when broaching the subject of the urban renewal that caused this Terry doesn't mince words,

Terry Baccus (20:12):

There's nothing worse than a massacre, but it's right up there because there's no more real life in Greenwood as it was, uh, in 21, as it was when they rebuilt back in 25, as it was in 35, 45, 55 in 1965. So it, it, it, it just, just took the life out of Greenwood cause of the highway system and urban renewal and eminent domain, we wasn't able to rebuild. After the massacre we was able to rebuild because we owned the land. And like I say, land is power.

Evan Stern (20:51):

Walking the grounds of OSU where benches, plaques and occasional monuments stand in place of businesses and homes, I can understand his feelings. Surrounded by parking lots and wide expanses of grass, Terry rattles off the names of streets this avenue once intersected. Eastern. Independence, Jasper, Marshall. None are left. And standing under an overpass. it pains me to learn of the beauty that was demolished in the name of this so-called progress.

Terry Baccus (21:23):

This is where the Dreamland Theater sat, right? It was a movie theater, Dreamland Theater was a movie theater. That was one of the grandest movie theaters in the Southwest or Southern United States. However you to put it for any people to, to own and operate, whether you black, indigenous white, European, whatever it was, grand and great. And so they built it.

Evan Stern (21:52):

And now there's a highway.

Terry Baccus (21:53):

Of course, there's a highway true

Evan Stern (21:55):

Today, the grandest building you'll find around here is of course the impressive Greenwood Rising history center, which sits about a hundred feet south of us on the corner of Archer. A museum that tells the story of Greenwood through film and a host of experiential audio, visual elements, they just had their ribbon cutting last summer. And speaking in a conference room near its entry, Phil enthusiastically tells me of the space's interactive experience,

Phil Armstrong (22:23):

Uh, in the first exhibit, the Greenwood Spirit where people learn about this history and learn about how Greenwood got started. Um, there is a feature in the floor, uh, that are a depiction of railroad tracks and seemingly they seem insignificant. But when you understand the role of railroad tracks back in the south in a deep south, that railroad tracks were the racial dividing line. Um, and so we created those railroad tracks as a depiction of you actually walking back in time, you are walking across the railroad tracks and coming back into Greenwood. Uh, it's, it's a very, when we explain the significance of those, it really has an impact of the racial narrative and backdrop in our country that it's always been here. And this is a place that tells the story in the right way, that this is a part of our history.

Phil Armstrong (23:08):

Good, bad, and ugly racism has been a part of the fabric of, of the country. It's just refusing to sit back and let someone say, I don't want to talk about that cause that's uncomfortable. Well, this is uncomfortable history. And if you can figure out a way to teach about racism and do it in a comfortable way, you're not teaching it correctly. So we're teaching history, but we're teaching it in a way to build people to an understanding that we have a, we've made a tremendous progress in, in inroads for, for racial development and equity and inclusion, but we still have a long way to go

Evan Stern (23:44):

All the same, this project has attracted its share of cynicism. Terry has yet to visit. And while he says he will and expresses respect for their intentions, confides, he worries the center is gentrification disguised as a reparation. But in response to this and other skeptics, Phil insists, this center is intended to be part of a broader conversation.

Phil Armstrong (24:08):

We do not agree that private donors and private citizens should abdicate the responsibility of those who were responsible. The 1921 Tulsa race riot commission for that was formed from 1997 to 2001 submitted to the state that the state, the national guard, the Tulsa police department, and those that were in power were complicit in everything that happened and they're liable. And they gave five recommendations of things that should be done, which included direct reparations to the descendants and their survivors. So here we are 20 years later and not one state policy initiative has ever been enacted to fulfill on the report that the state paid for. No private citizen or private donor should take the place. That's like saying, "Hey, it's your fault, but I'm gonna pay for it." No. Private donors and citizens said, let's put the money together so that the city of Tulsa and Oklahoma can no longer hide this, build a world class Smithsonian style center, where people come from all over the world and see what happened here. And then question, why hasn't the state followed through on that commission report that's 20 years old? You are liable.

Evan Stern (25:24):

Additionally, Hannibal argues as well that the lessons of this history reverberate well beyond the borders of Tulsa,

Hannibal B Johnson (25:30):

I've said many times what's really important to me is the Black Wall Street mindset. So it's not something that is more geographically to this physical space. Um, it, it, it's a psychological dynamic about the capacity of black folks to be successful in economics and entrepreneurship. It has to do with African American history around success and economics and entrepreneurship that we largely don't know about. That if we did know about, we could leverage to our own advantage.

Evan Stern (26:00):

I was grateful to find this mindset alive and well, a few steps away at Wanda J's Next Generation whose owner Ty Walker found time to speak with me before prepping today's menu.

Ty Walker (26:12):

We, you know, some people call it soul food. Some people call it Southern cooking. And I say, it's food to make sure your swimsuit stay on when you get in the water. <laugh> So if you eat a, a mustard green, it's supposed to taste like a mustard green, you know? And so we make sure it tastes what it's supposed to taste like. You know, we don't try to sugar coat it or make it, you know, what I call the, the chef type stuff, create little dishes and certain tastes and things like that. We take everyday basic everyday foods and cook them properly and make 'em taste good.

Evan Stern (26:42):

Having treated myself to a plate of fried chicken, mashed potatoes, cornbread, and green beans, it's hard for me to disagree with this assessment. You'll find Ty most days busying himself in the kitchen of this low frills, but welcoming cafe at 111 North Greenwood. A tall, handsome goateed ex serviceman, he tells me he learned how to work a grill at age eight and opened this outpost in 2016 with his daughters, hence the subtitle "next generation." But he's also sure to let me know he wouldn't be here if not for his mother who started this all nearly 50 years ago,

Ty Walker (27:19):

Wanda J is my mother. She actually started in 1974, uh, about a mile mile, mile and a half further north on the corner of Apache and Peoria. And I was eight years old and she was 24 years old when we started this. And so I have more experience than she do. <Laugh> But that's where it come from. She, uh, uh, was a single mother, single parent for say, had two kids. Uh, she was working, uh, for a restaurant. She was a, a short order cook for a restaurant in south Tulsa there. And, uh, I was in the first grade, I got hit by a car and, uh, hospital thing. I ended up in a full body cast. Triy to hurry this up. But the true story- I was being released from the hospital and the gentleman that she was working for that owned the restaurant, told her she was able to clock out and go have me discharged from the hospital, but she had to come back and finish her shift.

Ty Walker (28:16):

And, uh, I, she did that. She went back and finished her shift. And I remember I was in a 63 Chevrolet Impala, four door. And I laid in the back seat in a full body cast. And my sister was in there and she was kind of help. And my mother came out and she said, man would never tell me how to control my life when I could work. And when I can work for her on that. And she's never worked for anybody else since then. And so she left that, uh, restaurant and started her own. The most important thing she always told me was if you make a friend today, you have a customer for life. I've never learned that it's never been in any book I've ever read or anything like that outside of the Bible, but <laugh>, but that's what she taught me that you make a friend today and have a customer for life.

Evan Stern (29:02):

Ty and his daughters have made me feel like a friend and the life they've brought to this block is worthy of patronage and celebration. It's my hope their success can encourage and inspire others and that someday I will return here to find more in the way of entrepreneurship, nightlife, and activity. I also hope I will live to see the remains of victims and mass graves located and the recommendations of the massacre commission's 2001 report honored. That means scholarships, business incentives, curriculum reform, and compensation for descendants and today's three survivors,

Dr. Scott Ellsworth (29:41):

National Geographic magazine this past summer put out a study and they tried to estimate how much generational wealth would be in Greenwood today had the massacre not happened. And they came up with a, a figure of $630 million. That is generations of house down payments, college tuition, seed money for new businesses, elder care, childcare, you name it. And, uh, that that's all gone. You know, the massacre was a, a discreet definable event. You know, we know who lived in Tulsa at the time. We can figure out if someone is a descendant or not, there will never be enough money to replace the loss, but we need to do that as a society.

Evan Stern (30:29):

I agree. This is something we as a society must do. Admittedly though, given our fraught political climate, I'm skeptical of how tenable these aims might prove, especially considering the last century of inaction. But where I, and I believe Terry, Dr. Ellsworth and the team at Greenwood Rising agree is that progress can only begin by meeting this history with honesty, no matter how difficult that might feel. Why is this important? Dr. Ellsworth quotes, Faulkner, who once said "The past, isn't dead, the past isn't even past." I think there's great truth to that as are the first words I noticed when parking my car on Archer, which Hannibal references as our time reaches an end.

Hannibal B Johnson (31:22):

Well on the outside of this building, Greenwood Rising is a quote from James Baldwin and he says, "Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced." That's what we're all about. It's about facing the reality of our history and then using the, the, those learnings and leveraging them to make us better in the present. And certainly for the future.