Episode 7 - Postcard from The Rio Grande Valley, “Community and Conjunto”

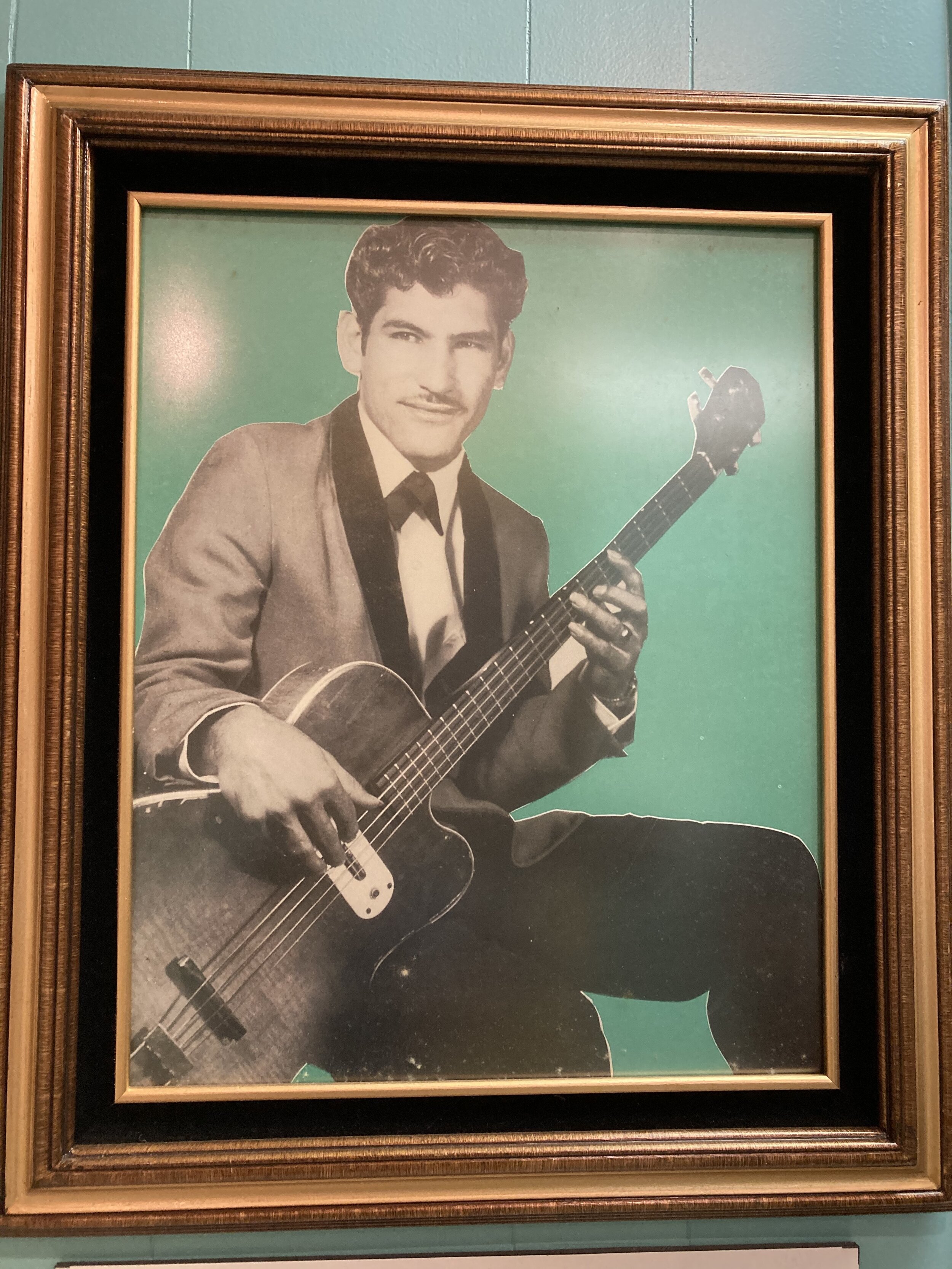

Rey Avila, 1942-2019

Born of the blending of cultures in South Texas, the music of conjunto tells a uniquely American story. In this episode, we’ll take a trip to its birthplace in San Benito to tour The Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame with the Avila family whose patriarch, Rey, dedicated his life to preserving this art form’s history. We’ll also head over to McAllen to catch a performance from accordion phenom Rodney Rodriguez at La Lomita Park, the venue built by famed performer and elder statesman, Pepe Maldonado.

The Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame

TRANSCRIPT

(As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos, spelling and grammatical errors)

________________________________________________________

Evan (00:00):

At the start of this adventure, it probably would have been a fun idea for me to keep a running tab of the distances I've traveled. As best I can figure, retracing steps in my head, I've probably driven upwards of 1500 miles so far. And in looking back on this all, I honestly can't think of any place I've been where I haven't encountered kindness. But when it comes to hospitality, the generosity I received in the Rio Grande Valley, humbled me beyond measure. I feel a need to bring this up because for years I've heard South Texas disparaged for its dull, brushy landscapes, and even recently read a fine writer describe this region as a purgatory and no man's land- not quite Texas, not quite Mexico. And when I saw that, I thought "this guy has gotten things terribly wrong" Texas once was Mexico and Mexican culture is Texas culture. For Heaven's sake, my heritage is German, Irish and French, but I've never known a Christmas that didn't include tamales. But better yet, it was here in this region below the Nueces and above the Rio Grande where different people came together to create one of the most quintessential Texas art forms. I'm talking about conjunto. And if you don't know what that is, well, get ready for a treat. I'm Evan Stern. And this is Vanishing Postcards.

Evan

As the crow flies, San Benito sits about sixteen miles north of the border in Cameron County between the cities of Brownsville and Harlingen. Founded in 1907, this one time railroad boomtown is about as south as South Texas gets, and Peter Avila will tell you his family has been here for quite some time.

Peter (02:34):

I'm named after my grandfather Pedro Avila. And then his father, Crispin was the original person that moved here, which he came from San Luis Potosi. So it was Crispin, Pedro, Reynaldo, myself and now Julio. So that's five generations, and and now with my Grandson, we're going on six.

Evan (02:57):

Peter's taking turns, playing guide from the backseat while his son, Julio, a 27 year old animator who's down visiting from Austin, drives us around in his Kia.

Julio (03:08):

That's right now we're turning right, going northbound on stinger street and, uh, to our left, we're passing the hotel Stonewall Jackson named after the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson. Uh, and this was one of the most popular hotels in the twenties, but it's been pretty much in varying states of decay since that time. Um, and it's been boarded up for a few years now, but it used to be a popping place. So I'm told.

Evan (03:31):

Much of San Benito used to be popping, they tell me, but like the hotel Stonewall Jackson, most of its downtown now sits vacant and boarded up.

Peter (03:41):

So all these little doors at one point were all bars that had music. Everyone had live music going on. So from here it was like a mini sixth street-

Evan (03:57):

Apart from a wandering dog and group of old men and plastic chairs at the corner of Bowie and Robertson, things seem pretty empty around here for a Saturday morning, but looking around Julio takes in this scene with more honesty than nostalgia.

Julio (04:14):

But that's the story of America. You know, this is just something that has happened all over the country when it comes to the conglomeration of big business and how that affects the small towns. You know, I mean, this is a story that's being played out in Ohio, California, any one of the 50 state., Essentially what you had is you had people coming to populate an area and then there's reactions and counter reactions to who is really ethnically making up this area. And so part of it should be said that like people stopped coming, businesses stopped coming, white flight, people started leaving. And now if, if you really do the math, the schools are made up. It's probably 96% Hispanic, 3% African Asian and Caucasian. So it was also something of that. I know that that had to have had an effect where the money leaves the city. And a lot of what we're seeing is kind of a result of the brain drain and the financial drain of those people moving onto more prosperous towns like Harlingen, McAllen, Brownsville, or further up north to Corpus, to San Antonio, to Austin, to Dallas. People go where they can make their money.

Evan (05:26):

I think there's a lot of truth to this. Similar communities can be found in Pennsylvania, Georgia, and just about anywhere. But towns like these, didn't just export cotton, metal or timber. They exported culture and art. Detroit gave us Motown and Clarksdale, Mississippi, the blues, but San Benito gave us conjunto!

Speaker 4 (05:56):

Henry Zimmerle- Llorar, Llorar plays

Rick Garcia (06:30):

I would have to say that San Benito is the, uh, is the nucleus for conjunto music. This is, this is the hotbed. Just like there is a Nashville for country. There is a Memphis, there is, uh, uh, Philadelphia for the rock and roll sound or whatever the, if you're, if you're really gonna get into conjunto music, this could be heavily debated, but no doubt San Benito is, is the nucleus. Uh, the, the, uh, the gentleman who's credited with starting the music is named Narcisso Martinez. And he was right from this area. From here one of the very first record labels spawned. A there's a, there's a dance hall that is just historic. Anybody who's anybody performed at that dance hall, it's called La Villita. Uh, the, the, the pioneers, which are Tony Delarosa, Valerio Longoria, Ruben Vela, Henry Zimmerle, uh, Steve Jordan, even Freddy Fender, Baldemar Huerta, was a great big part of this back a long time ago. And, and it is, it is, it has continued to grow and it's continued. Now we're seeing a knowledge and a resurgence of where it actually came from of the birthplace of it.

Evan (07:46):

That's Rick Garcia, president of CHR records, a label that boasts some of the finest conjunto artists in the business.

Evan (07:55):

We're speaking at a round table in the office of the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame. Julio's there, while Peter sits to my left next to his brother, Joe and sister, Patricia. This museum was founded some 20 years ago by Rey Avila, their recently departed father who made the promotion and preservation of this music his life's work. Since his passing a mere seven months ago, the Avilas have stepped up their involvement in the museum. And when I asked them to tell me about the family patriarch, Joe was quick to chime in-

Speaker 6 (08:27):

What I remember about him. I guess what got him into conjunto. A lot of the employees that worked with him were musicians. They played accordion, they played the drums. They played the bajo sexto, and the employees would work 40, 50 hour weeks with my dad hard work at the end of the day, they'd go play at the bar. They'd play till one, two in the morning and come back Sunday. We had to work on Sunday or a Saturday back at eight o'clock and worked that hard day and go back again. But they'd come back and they'd start telling the stories. So that's, I guess my dad started getting pieces from there. And that's where, you know, that little time of working with those musicians really brought up a lot in our interests. My dad was never a musician. You know, he can't read music. He never played an instrument, but he's a historian. And he, I guess he felt that he needed to tell the word, you know, tell, tell the people, uh, the history of conjunto. And that was his, uh, one of his, uh, um, inspirations to doing this.

Evan (09:40):

But what is conjunto music? A cursory glance at Wikipedia will tell you the word literally translates to group or ensemble, that it was born in the early 20th century when Mexican and Tejano laborers adopted the polkas and button accordions brought to Texas by German settlers. They gave Spanish lyrics to these melodies and threw in some guitar from an instrument called the bajo sexto. Its godfather figure was San Benito's own Narcisso Martinez whose accordion you're hearing now in his recording, muchachos alegres. That's the cliff notes version, but Julio cuts to the heart of the how and why all of this happened with far greater eloquence.

Julio (10:19):

It's an American invention. It comes out of the meeting of two separate cultures in Texas. You had a lot of peoples stories. My grandpa told me of people going up north traveling to meet family and distant places, and they're encountering the polkas, the German polkas and the accordion music and the big band brass music of the time that was popular in north Texas, at that time in the hill country. They're bringing these ideas and sounds that are making people happy to the valley. And then they're trying to get that energy going again, but it has to be something that's organic to themselves because they're the ones playing the instruments. And it's out of that necessity that this music is born. You know, it has a four, four beat the rhythm a lot of times. It's supposed to be happy music that makes people want to move. And it brought communities together, communities here who were dealing with a particular, you know, societal thing that is still kind of affecting us here, which is, Hey, we're two different people. And we got to live together. Let's let's communicate musically that might help.

Peter (11:23):

Something my dad would always tell us, is it all had to do with them having to go pick, uh, go, do strawberries, go do cotton and go do wherever they had to travel. And a lot of times, if it was traveling in central Texas, well, they were young and they wanted to go have fun. So they would find out where are the places and that's where they would put the ear to the music. And it seems like through just the experience of them being out there exposed, is how it started to grow

Evan (11:55):

One kid who was out picking cotton back in the early 1950s was Pepe Maldonado.

Pepe Maldonado (12:01):

Uh, we used to go when I was, let's say, uh, 12, 13 years old, we used to go- we were migrants. We used to go up north, pick cotton and go from one place to another. We used to go to let's say from here Robstown and from RR from Robstown we'd go to El Campo. We go to, uh, go close to Dallas, Waxahachie, or west Texas. And, uh, one time it was so hot and this is the truth. I swear to God, I'm gonna tell you the truth. Uh, I was picking, picking cotton so hot and I was 13 or 14 years old, 13, somewhere in there. I said, no, I got up. And I said, "You know what? This is not for me. I'm going to be an artist. I'm going to make people know who I am. I'm going to sing." And believe me. It came true. That moment. I made the decision. I was going to do it. And my dad was against him. He didn't want me to sing or play or whatever, but he, he, after, after he heard my first record here, he said, "Damn, you know how to sing." I remember that.

Evan (13:05):

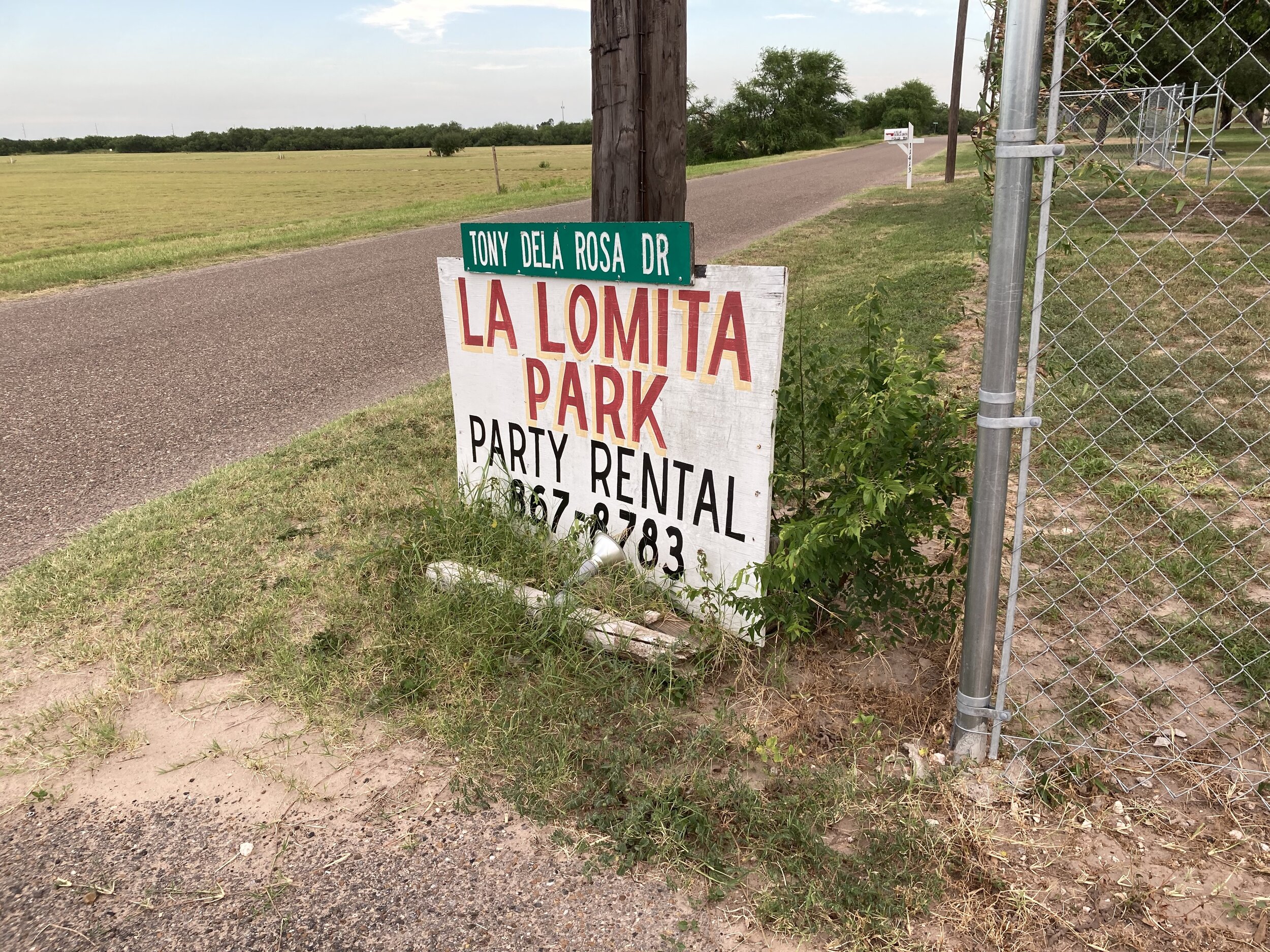

Pepe made good on that promise, rubbed elbows with greats like Ruben Vela and Narcisso Martinez and embarked on a successful career that carried him all the way to the white house lawn and an audience with Bill Clinton. Nearing 80, he doesn't sing much anymore, but can be found most every Sunday at La Lomita Park, the venue he built practically with his own hands outside McAllen. In addition to San Benito's famed La Villita, I'm told this is one of the great spots in the valley to catch conjunto live. And it's where we're talking tonight. Pulling in here is surreal. Its driveway is named for the accordion master Tony de la Rosa. And on the left, you're greeted by a sign that reads Hard Times, Texas population 16. The main building on the right is unmissable. As it's made of false fronts with names like tombstone hotel, to give it the look of an old Western boardwalk. Opening the door, you'll find Pepe's wife, Irma sitting next to a jar of holy water, ready to take your $5 cover while their daughter, Diana is busy in the kitchen, serving up tacos, enchiladas and burgers. Though the lighting is dim and the AC cool, the spirit here is warm, friendly and familial, which is why tonight's entertainer 36 year old. Rodney Rodriguez tells me this is one of his favorite places to perform.

Rodney Rodriguez (14:28):

Okay. Well, the perfect night at La Lomita is when, like, Pepe Says (speaks in Spanish), that means that it's full. And that's what we like to see here at La Lomita. Hopefully tonight it will be full also. And that gives us the musicians playing well, a lot of gusto, you know, and a lot of joy. And that's what we want to see. Well, here, everyone becomes like family. Cause uh, the same people always come here. They love getting together here and we know them all. We know. We know pretty much everyone that comes here by name and that's, that's, that's a great thing.

Evan (15:03):

A native of nearby Rio Grande City, Rodney is modest, soft-spoken and about a head shorter than me, which trust me, you don't see often. But the guy is a beast on the accordion an instrument he fell in love with as a kid that took him all the way to a two week residency at the Smithsonian Institute.

Rodney Rodriguez (15:24):

Uh, the one I can never forget is performing at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. We were with there for two weeks and that was beautiful. That was a beautiful experience. Well, it was great. Cause I mean, every, everyone was dancing at their own style. You know, like you say, there was Chinese people and African-Americans and everything. We, they all were having fun to our, to our style of music, you know? And, and that's great that that made us feel very good.

Evan (15:53):

Like Julio, he credits his grandparents with introducing him to conjunto and tells me that the mission of his group Los Cucuyus is to keep conjunto alive.

Evan (16:03):

And when you're not performing conjunto, what are you doing?

Rodney Rodriguez (16:07):

Uh, listening to conjunto, trying to bring out more old songs. I mean, I love oldies and that's what we try to do here with Los Cucuyus to bring back old songs that haven't been heard for a while. We're a straight conjunto a hundred percent conjunto. And, uh, we try to keep up the legacy of the old guys, the legends Gilberto Perez, Ruben Vela, Tony De La Rosa and all that good stuff. Uh, and that's what we have it's just old school conjunto.

Evan (16:41):

Pepe and Rodney expressed to me that they worry about the endurance of conjunto. Right now, hip hop does seem to be all the rage on both sides of the border. But while Diana confesses to me in the back that this music is her father's, not hers, she says the young people in her life are actually conjunto obsessed.

Diana (17:00):

I'm not really into conjunto. My daughter is a fanatic. Rebecca, she's a fanatic. She knows everybody and everything. I'm here to support my dad, no matter what he does, we're here to support him. And I love his music. His music is great.

Evan (17:15):

How old is your daughter?

Diana (17:17):

35. Yes. Uh, my nephews, my, uh, my daughter, all the grandchildren are really getting raised with all this. They were raised with it. They know what the music is. Uh, they all know the names. Like I said, they they're fanatics. They are all into conjunto music.

Evan (17:34):

Hearing this, I think of Julio who told me yesterday that, while conjunto might not be his first music of choice, it's home.

Julio (17:43):

I'm a little younger. So I'll speak from this perspective. When I, when you're growing up, I feel most people make a decision. Do you really like conjunto music? Do you really? I mean, your grandpa does, he made that clear in the car. You know what I mean? So, so years later, I'm, I'm 27. Now. I slowly it's like he says it, it goes away. It comes back. I'm in Austin, I'm driving through Austin. Uh, sometimes I feel so homesick. I'm listening to conjunto on the radio. I never would have done that as a kid. I just know, you know, but it reminds me of the times where you're, uh, here in The Plaza and there's the community's here. There's vendors. People are selling people that are walking around people, having a good time with their family and you, you feel like you're a part of something. And here it can be hard sometimes outside of your family groups to find that community. But the music's always that spot where we can go in. So even someone I'm not a daily connoisseur of the music, but it means something to me in that way, like in a deep, spiritual way now that I couldn't put words to before. And actually, you know, it didn't matter that much before

Evan (18:46):

The ages are mixed tonight at La Lomita and with Rodney Rodriguez y Los Cucuyus on stage, I'm easily one of the few seated and decide to make a discreet exit. But before I can slink away a spirited, bespectacled gentleman by the name of Pablo Puentes beckons me to his table.

Pablo Puentes (19:05):

Conjunto music is the best music for everybody. Old, new, the one that's going to be born. Because conjunto music has got a lot of folklore, and you're going to be so happy with what the word says and the way you dance to the music. It's love. So conjunto music is the best and it's still alive. Never say it's dead. Conjunto music will never die. Always be alive.

Peter (20:23):

Here's where he has the, the founding fathers. This on this side is Narcisso Martinez. And over here, it's Santiago. They're the two that originally put the ensemble together, him bringing the bajo sexto and he brought in the, the accordion

Evan (20:42):

Back in San Benito, Peter and Rick are leading me on a walkthrough of the hall of fame. It's a simple space housed in a downtown community, building. Portraits and biographies of inductees cover the walls while a few artifacts from the original ideal records decorate a side room.

Rick Garcia (20:59):

And can you imagine the recording systems used to look like this back in the day? It's like one track, possibly two tracks. And that's it? No overdubs, no 16 track, no 24 track, whatever. So you got it right when you had to do it again, one track. And I would hear the stories. They would say that, oh, they'd get a recording that was almost so good. And then all of a sudden it's over with and a train goes by. Oh my goodness, there they go. They chunk that acetate and you have to do a new one.

Evan (21:28):

While they host an induction concert and celebration each year, you won't find the interactive features or sleek bells and whistles found at the rock and roll hall of fame here. But Rick will tell you that for those who love conjunto, though, this place is sacred and needed.

Rick Garcia (21:44):

There is as much passion in this, as there is for people like that, like the Etta James music, they go to those museums, the people that like Elvis Presley and go to the sun records museum. Thank goodness there's a museum here for the people that love conjunto music. It's every bit as special and every bit as passionate

Evan (22:04):

Again, Rick stresses that the reason this all exists is because of Rey Avila.

Speaker 5 (22:10):

The one thing I, I don't, I don't want to see happen is for Rey Avila's vision to, to, to stop, you know? In fact, thank goodness his family and his kids are behind it. And, uh, out of all the associations that I've been involved in, and I've been involved in a lot of them- there is none, there's none as authentic as this one. And if anything, I mean, I wish they, I wish all of them well, but this one here is, as you can just tell how it's so well put together. And each artist tells a story.

Evan (22:50):

Mr. Avila is absolutely deserving of this praise as this space provides an incredible record of the important legends who've made this music, what it is. I regret the timing of this project was such that I didn't get the chance to meet him. Patricia tells me he would have welcomed me with a warm smile and countless stories, but also sees some poetry in the timing of my arrival.

Patricia (23:13):

I think it's so beautiful that this interview is happening on Father's Day weekend. It's gonna be a hard weekend for us, but, you know, he left us so much, so many good memories and so much to treasure. Family was so important to him, just as much as conjunto music and thank God most of us, we all do appreciate the music. And we've gained so many good friends that are right there holding our hands along the way,

Evan (23:39):

I'm grateful the Avilas seem committed to picking up the reins of this operation. And it's my hope they can inject the hall of fame with new energy. Sure. Though, Flaco Jimenez and other artists have recorded with the likes of the Rolling Stones and David Byrne, I can see how some might say you don't often see conjunto topping the charts. But it is representative of a uniquely American story that deserves our collective respect. Making this museum the destination it deserves to be, might take more time, money and effort than the Avilas and San Benito can provide on their own. Patricia is a teacher and Joe and Peter work in property appraisal. But how great would it be to return someday to find headphones below the portraits where visitors could hear music from the legends themselves, or tour a recreation of the original Ideal Records. For now, though, Peter and Julio drive me by the building where the greats once gathered in a back room to create.

Peter (24:44):

The old record company was right here where now it's the Victoria's, uh, party hall. So in the front, uh, right where the sewing boxes, that's where used to be the record store itself. And then the back is where they would produce the records. And that used to be the fire station. So you could see how I would ride through the back alley. Cause I like to see the fire station and then through the back of the building, here's where they would throw the old records that I guess wouldn't make it. So I would go through here and I could hear the music right here. I could hear jamming.

Evan (25:14):

Julio then tells me a story of how, when he was 15, he and his grandfather finagled themselves inside.

Julio (25:22):

It was like a time capsule. Nothing had been moved since the day production had stopped some 50 years, 40 years before. So I'm this teenage boy. And I'm looking at this for the first time and I'm getting a grasp of like my grandpa's not crazy. This used to be a real thing. It's like, oh man history came to life for me that day. And all the recording equipment was there. And I'm telling you thousands of recently pressed, mint condition recording vinyls that had just- it's like people had vanished almost

Evan (25:50):

After passing this site of many memories. We began to drive back towards our starting point and a pregnant pause, settled in the car. I had to ask a question. But is it hard for you to see all this abandonment?

Peter (26:05):

Well, it is, you know, I've been here 52 years and you know, I've, I stayed home because of my family. You know, I've always asked myself what would be different if I would've left, like some of my friends, but that is, I mean, it, I love it here. I really do. You know, and no matter church, wherever I go, I help run the league of baseball. Um, you really get a grasp of community every time, every day. You know, one thing I noticed in just the world of living and being, it didn't ever matter where I went to a business meeting in Atlanta or a business meeting in Las Vegas, one thing I always found as a common denominator is that as you got to visit these places, you always knew that you would run into the hardworking persons, whether at the restaurant or the housekeeping, but as, as, as soon as you talk to them in Spanish, they were back home.

Peter (27:07):

And one time in Atlanta. I'm there. And I was with a coworker and we hadn't had were there two weeks training and we wanted to have huevos rancheros. Original. And we noticed that the lady was Hispanic. And so we said, ma'am, y'all don't have any huevos rancheros. And she says, "Oh, the cook in the back, the chef, he makes real good huevos rancheros." And so I said, "You think he'll mind?" No, sir. So she goes back there and she brings us some of the best huevos rancheros. We ate and we smiled. And at the end I said, I want to go meet the chef. And so I went back there, it turned out he's from the valley. And he, we just had a good old time. And every kitchen, if you put an ear to it, you're going to hear a good , conjunto music because it takes us back to the, to the, to the ground, which is where it all started. And it all started in towns like this, you know, and that's powerful. I always found that to be real powerful.

Evan (28:14):

That's a wonderful note to end on. And again, I thank you so much. This has been a wonderful, rich morning.